As the Civil War raged on for four years, four holiday seasons came and went. Famed illustrator Thomas Nast created enduring depictions of Christmas for Harper’s Weekly, giving us a sense of what celebrating Christmas amid the Civil War was like. Keep in mind, Nast was a political cartoonist and somewhat of a propagandist tool, and it’s not lost on the viewer which side he staunchly supported.

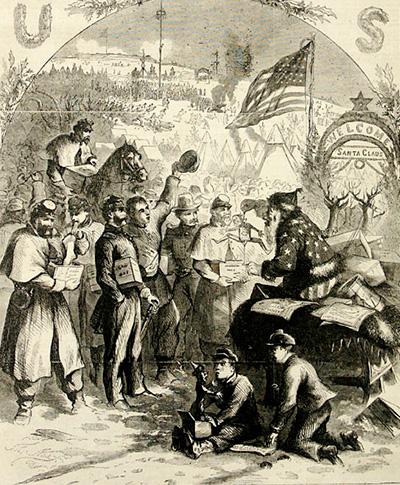

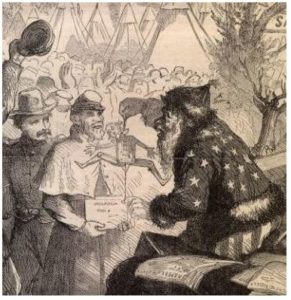

Santa Claus in Camp

The January 3, 1863, cover of Harper’s Weekly featured a sketch by Thomas Nast called “Santa Claus in Camp.” The image depicts a Santa Claus with a long white beard, striped trousers, star-sprinkled jacket, and a furry hat, sitting on a sleigh being pulled by reindeer. He’s handing out gifts to children and soldiers. Note the rich details, including the soldier receiving a new pair of socks and the drummer boys in the front playing with a jack-in-the-box. But what’s really fascinating is the fact that Santa is holding a puppet resembling Jefferson Davis hanging in effigy—an example of Nast’s role as a political propagandist. The text states: “Santa Claus is entertaining the soldiers by showing them Jeff Davis’s future. He is tying a cord pretty tightly round his neck, and Jeff Davis seems to be kicking very much at such a fate.”

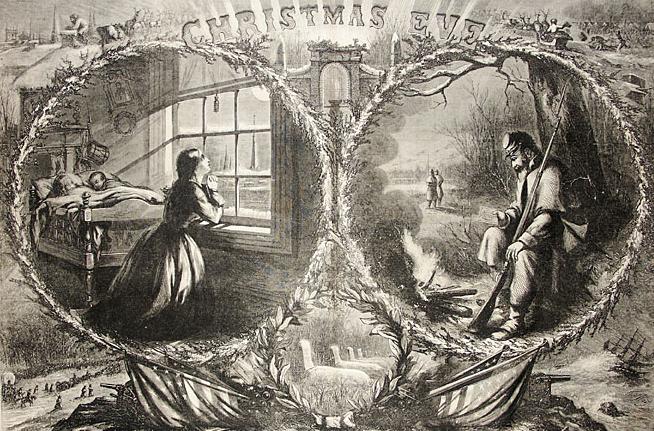

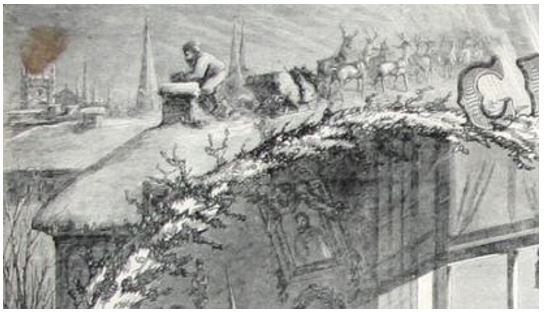

Christmas Eve

In this double-circle picture, entitled “Christmas Eve” and published in the December 26, 1862, edition of Harper’s Weekly, Nash shows a wife praying through a window for the safe return of her husband. Adjacent, her husband prays in front of a flickering fire on a battlefield, looking longingly at photos of his family. Santa appears twice in this picture: on the left, climbing down a chimney, and on the right, riding a reindeer-pulled sleigh over a Union campground, tossing presents as he goes. On the bottom left, refugees flee war, while on the bottom right, Union naval ships are being tossed by an icy storm. Newly dug graves in a cemetery are depicted in the middle.

Christmas

After the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Christmas was a time of homecoming. In the three-part drawing, which was published in December 1863 in Harper’s Weekly, the soldier is home on leave, greeted by his loving wife in the center frame. On the left, Santa bends of their sleeping children with a sack full of toys, and on the right, the children open their gifts on Christmas morning.

Merry Old Santa Claus

Nast was applauded for his depictions of Santa Claus, and he was asked to provide a Santa Claus illustration for Harper’s Weekly nearly every following Christmas. Before Nast, Santa was a skinny guy with a trim brown beard, based on the Christian St. Nicholas. Nast turned him into this jolly old man, which appeared in Harper’s Weekly in 1881 and continues to be our model for Santa Claus. The magic of Santa Claus was born.

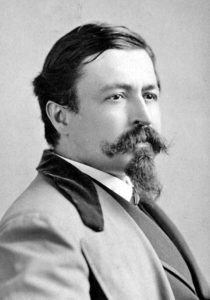

Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast was born in 1840 in Landau, Germany, and was forced to flee to the United States with his family at the age of five thanks to his father’s political beliefs that were at odds with the Bavarian government. Nash went on to study art, with his drawings first appearing in Harper’s Weekly in March 1859, at the age of 18. While his Civil War–era drawings are powerful, and his Santa Claus depictions forever etched on the American psyche in his rendition of Christmas’s secular centerpiece, he is best known for attacking the political machine of William M. Tweed in New York City in the 1870s. He is considered the “Father of the American Cartoon.”