I was a seven-year-old boy who had never thrown a baseball, been to a baseball game, nor had Roger Maris hit 61 home runs or the Reds and Yankees tangled in the 1961 World Series. The Centennial commemoration of the American Civil War was underway, and National Geographic magazine, Volume 119, Number 4, dated April 1961, was part of an $8-a-year annual subscription. It came free with a $6.50 nomination to “Membership” in the Society.

National Geographic had a huge reputation. Its Board of Trustees was a Who’s Who of American society: Chief Justice Earl Warren was on it, as was Gen. Curtis LeMay of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Vice Chairman of AT&T, the Secretary of the Treasury, the Vice Chairman of NASA, the Director of the National Park Service, and more. Cunard, Lincoln Continental, and Ford Thunderbird were all featured advertisements; sketches of Abraham Lincoln and Robert E. Lee were accompanied by a claim that they both entrusted their futures to The Hartford Insurance Group.

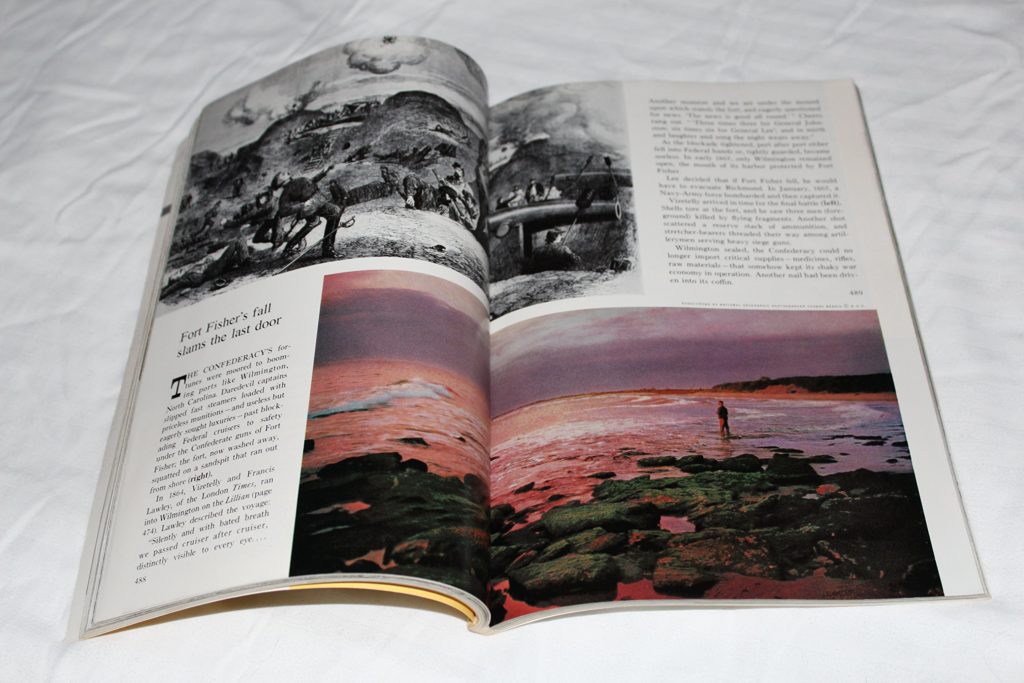

With a titanic struggle now exactly 100 years in the rearview mirror, National Geographic led this edition with three articles over 55 pages. The first story was written by the grandson of the Commander of the Union Armies, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant III. A second teaser piece introduced a spectacular map supplement “Battlefields of the Civil War.” And finally, a detailed piece showcased the observations and writings of British correspondent Frank Vizetelly, who chronicled the war.

It would be the first of three magazines over the Civil War’s centennial leading with the Civil War.

The second was Volume 124 Number 1 in July 1963, featuring two more articles, one by Carl Sandburg and the other led by Robert Paul Jordan (author of The Civil War that was published by National Geographic later in the decade). Those 54 pages detailed Gettysburg and Vicksburg—signal events in the great struggle (cooperation on that article came from a then-little-known WWII wounded warrior named Ed Bearss).

The NGS treatment ended with Volume 127, number 4 in April 1865 with a 35-page leading essay by Grant on “How to End a War, Grant and Lee at Appomattox.”

A Magazine Review

I found it useful to look first at all the images and read the captions and/or sidebars before reading the narratives without those intellectually distracting visual stimuli. What I was impressed by was the universal respect for the southern cause, albeit a wrong one, that was projected from this Washington, D.C.-based international organization. Clearly, the two most noble characters were Lincoln and Lee, a tag team of integrity that comported well with the “Ozzie and Harriet” and “Leave it to Beaver” society—pre-Vietnam. To appreciate the calm-before-the-20th-century storm, you must be old enough to appreciate that the USA had reunited and grown into a world power. We had fought the Spanish–American War, in which Confederate veterans had shouldered guns next to former enemies. We had been “Over there” in World War I, and the country had been the arsenal of democracy for World War II. We were just out of an unprofitable war against the surrogate armies of our new ideological enemies—the Soviet Union. The Cuban Missile Crisis was yet to come.

Our Changing Society

What changed was a roiling of society. Brown versus the Board of Education had set aside “Separate but Equal,” and white communities erupted with the court ruling that suggested that black children would go to the same schools as white children—in Little Rock, National Guardsmen escorted children of color as they integrated the schools. It was the beginning of a moral crusade that caused the streets to burn and tested generational beliefs in a separation of the races. In reality, a second Civil War had begun. Those realities, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and the emergence of an unlikely Civil Rights advocate, Lyndon Johnson, interfacing with modern-day Frederick Douglasses named Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy, marching with young idealists like John Lewis, provided the fulfillment of Lincoln’s moral vision. Voting rights acts and Civil Rights legislation paved the way for the actual end of “Reconstruction,” a 100-year process.

In a country that had worked hard to mend the wounds of internecine strife and had largely succeeded the same old wounds of war were torn open again with the demand and legal imperatives to treat the descendants of the enslaved men, who had been freed by presidential declaration and had served not only in the Civil War but every war since, with the dignity due to all men who were endowed with inalienable rights. I am 69 and I remember the wounds. I lived in Mississippi from 1965 until 1967. It has been a lot of years, and many lessons had to be learned the hard way—why did black airmen riot at Travis Air Force Base? It was because the military exchange system didn’t stock any black magazines other than Ebony and Jet. Within 10 years, I was sitting as a second lieutenant in “Social Actions” training in 1976 with my white colonel Wing Commander, as a black sergeant with an Afro haircut very pointedly telling us white guys that we didn’t get it!

What We Can Learn

So what can we learn from these 144 pages of analysis? First, the war is a very solid foundational element of the American Experience—even after four more wars, including two world wars. Second, society was on the cusp of a very rude awakening in which the white male community had largely kissed, made up, and moved on, while people of color and women waited for their turn. Third, Brown versus Topeka Board of Education heralded a sociological shift that created strong pushback. Southern states rallied and passed legislation that protected their established institutions, violence often substituted for compliance, state flags suddenly sprouted variances that contained some aspect of the old Confederate flags, and last but not least, the South generally hijacked the Centennial Commemorations and turned them into “The South will Rise Again” pep rallies. General Grant was a co-chairman of the National Centennial Commission. He resigned it midway, as the direction of the commemoration moved toward a celebration of the Old South. Subsequent analysis was rapidly swept under the carpet as the unrest of the late sixties consumed all rational discussion. The country was mad. It was going into a war in Vietnam that was drug-ridden and which disproportionately drafted young black soldiers whose parents could not afford to get them college deferments.

I read these essays more than seven months ago intending to feature them in April 2022. Instead, I found myself asking the next harder question and the question of “So What?” I think all historians and social scientists with an awareness of America in its Eisenhower complacency can benefit from getting the articles, looking through the magazines, and reflecting on who we were and who we now are?

Several months ago, I reviewed the NGS’s treatment of the Underground Railroad. What amazed me was the amount of time from this series that it took to write that set of articles—nearly 20 years. Forty years after that, Nat Geo, anticipating the publication of our first book with them (Ed Bearss’s Fields of Honor) in April 2005 published 24 pages on “Civil War, Then and Now, The Fight to preserve America’s Sacred Ground.” As they did 44 years before, they released a huge map of Civil War battlefields. From 2005 onward, BGES participated in publishing four Civil War books including a best-selling guide book (2016) that has now sold more than 19,000 copies.

A sociological trip worth taking.

You must be logged in to post a comment.