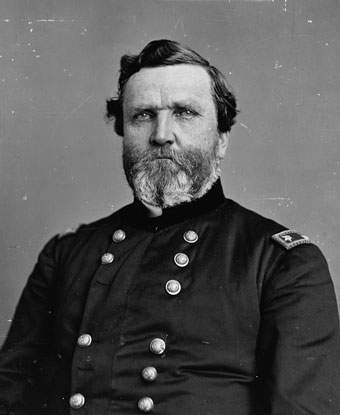

Historians might describe Gen. George Thomas as something of a cipher. He is the man in the plain blue uniform who comes to a party and yet no one remembers his arrival or departure. Thomas was in the thick of numerous battles: Chickamauga and Missionary Ridge, Chattanooga and Atlanta, Stones River and Mill Springs, Peachtree Creek and Nashville. And he is, and will always be, the Rock of Chickamauga, a failsafe warrior who turned the tide in Tennessee for the Union Army.

He never courted public accolades—he did not want them—and, accordingly, before his death in 1870, he instructed his wife to burn his personal papers to prevent historians from memorializing him.

He’s also been called a traitor.

So how does a biographer truly discover the essence of such a soldier?

Dr. Brian Steel Wills took on the challenge, resulting in As True As Steel, his definitive biography of George Thomas. The director of the Center for the Study of the Civil War Era and professor of history at Kennesaw State University, Wills set himself to the task of ferreting out a man who did not want to be found. He’d heard the stories and the ill-concealed loathing of his fellow Virginians. To wit, why as a Virginian, did Thomas pledge his service to the Union? He wanted a more complete understanding of what made sense to Thomas, using a 19th-century lens as a focusing agent. He found the epithet of traitor to be fascinating.

George Thomas grew up in Southampton County, Virginia, a neighboring county to Nansemond (now Suffolk, Virginia), where Wills currently resides. From there, Thomas went on to West Point.

“Thomas’s career was solidly rooted in the U.S. Army,” Wills says. “He served in Mexico with the U.S. Forces. When the Civil War ensued, Thomas stayed the course and remained a loyal soldier in the Union army.”

His fellow Virginians called him a traitor and held him in low esteem. Nevertheless, Wills says: “Ever true to his sense of duty, George Thomas overcame initial doubts concerning his southern birth to win the hearts of those who loved the Union as much as he did.”

And to simply call Thomas a traitor to the Lost Cause allows one to learn nothing, according to Wills. It’s a too-facile approach to a complex man, he says.

From the earliest days of his career, this complex man didn’t always garner respect for other reasons. He exhibited a desire for action, for offense, always predicated and prefaced by careful preparations to ensure victory. Thomas, according to Wills, never did anything that he did not think was absolutely right. He was a faithful, loyal, devoted soldier with a very subtle sense of humor that lay just under the surface. Thomas deeply held his emotions in check, hiding behind a strict and stolid demeanor.

During the Civil War, these characteristics drove the often-explosive U.S. Grant, a superior, and the flamboyant William Sherman, a colleague, friend, and fellow general, to distraction, which often diminished Thomas’s opportunities to lead. And so, he accepted a subordinate position to junior officer William S. Rosecrans in Kentucky and it chafed and festered. He still preferred loyalty and preparedness over a convenient chance to advance his own ticket.

Although Thomas trounced John Bell Hood at the Battle of Nashville, for example, he took no pleasure in the notice it gave him, perhaps because U.S. Grant was less than pleased with Thomas’s initial slowness to act. Because of a back injury from which he never sufficiently recovered, Thomas’s physical movements were slow and protracted, his steps deliberate and ponderous. There was no flair or élan. He was, in essence, a man who showed up and did the job requested of him.

That said, Thomas excelled at Stone’s River, and characteristically and laconically quipped to Rosencrans on the evening after the battle against Braxton Bragg: “General, I know of no better place to die than right here.”

This neatly sums up Thomas’s philosophy. His stubborn insistence to stick with his plan of attack prevented a Union defeat and won him the sobriquet “Rock of Chickamauga.”

As Wills tells it, Thomas remained obscured in the Western theater, often hidden behind other generals with a penchant for self-promotion. Thomas did not receive press coverage in national newspaper accounts. He was loyal to a fault, strong in the extreme, a character without the flash of fellow generals of his day. He performed his duty to the fullest and kept it to himself. He was ambitious, but without ruthlessness. Successful without an outward display of hubris.

Thomas went about his duties, pulling his own way, and with that, he’s rated as one of the three or four top fighting generals of his generation. Not bad for a man allergic to fame.

Brian Steel Wills is also the author of: Inglorious Passages; Noncombat Deaths in the American Civil War and The Confederacy’s Greatest Cavalryman: Nathan Bedford Forrest. He will be co-leading BGES’s tour, “All’s Fair in War, Streight’s Raid & Forrest’s Bluff,” on June 25–27, 2021.

You must be logged in to post a comment.