General McClellan’s major Union offensive against Richmond in the spring and summer of 1862 unfolded on the peninsula located between the James and York Rivers. The first stage ended inconclusively at the Battle of Seven Pines, where Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston was injured. With Robert E. Lee taking his place, the Army of the Potomac successfully warded off McClellan’s attack. These are the major sites associated with the Peninsula Campaign, easily accessible by car. Several are part of the Richmond Battlefield Military Park.

Beaver Dam Creek

June 26, 1862

With McClellan’s Army of the Potomac within sight of Richmond’s church spires, Lee took the offensive. Vastly outnumbered, Lee nevertheless created a masterful plan: In placing the majority of his army on his left, he intended to destroy the isolated Federal V Corps under General Porter. The plan promptly fell apart when Stonewall Jackson’s troops failed to arrive on time and an impatient Gen. A. P. Hill initiated the attack without his support. Although the Confederates suffered many more casualties, McClellan ordered Porter to fall back, ceding ground to Lee.

What to see: Multiple markers and walking trail are scattered about the preserved battlefield site.

Visitor info: Richmond National Battlefield Park, 7423 Cold Harbor Rd., Mechanicsville, nps.gov/rich

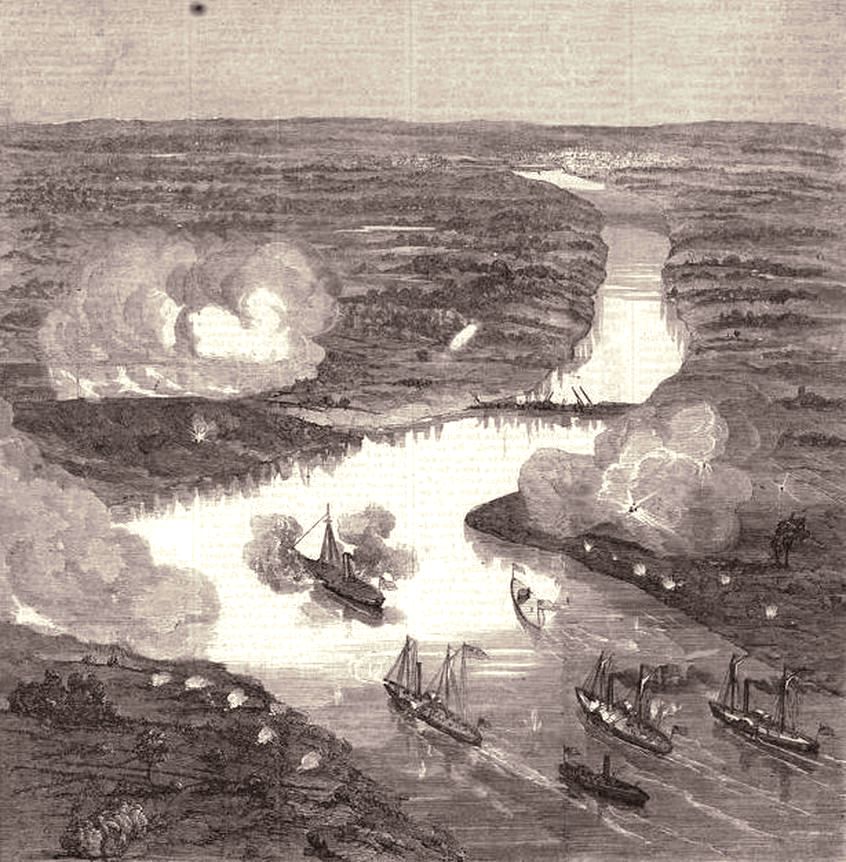

Drewry’s Bluff

May 15, 1862

After the retreating Confederates destroyed their ironclad Virginia, Federal gunboats steamed up the James River, looking to seize Richmond. They were stopped by Confederate batteries at Drewry’s Bluff. Ironically, the Union’s newly built ironclad monitors, although strong, were unable to aim their cannon high enough to attack Southern defenses. Facing strong artillery fire, sniping, and heavy damage to the iron-covered vessel Galena, the Federal ships withdrew.

What to see: There’s a short trail, several markers, and a river view at Drewry’s Bluff.

Visitor info: Richmond National Battlefield Park, www.nps.gov/rich. Take Bellwood Rd. to Fort Darling Rd. then go left for half a mile. When the road diverges, veer right and park in the cul-de-sac at the end of the road.

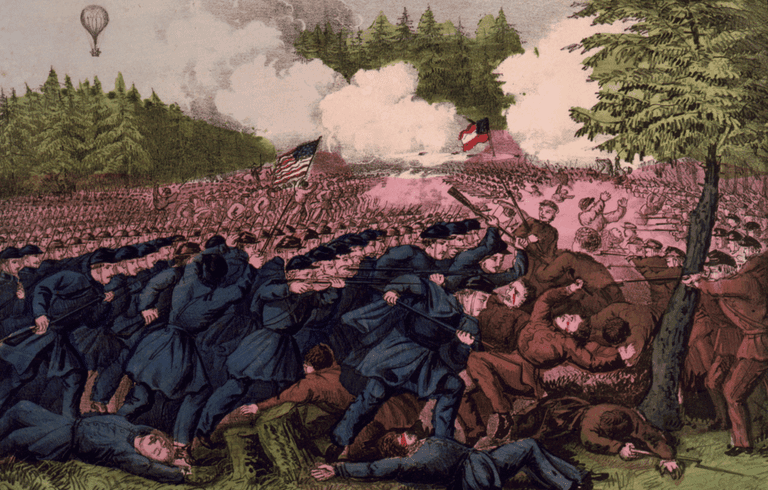

Gaines’ Mill

June 27, 1862

The third of the Seven Days Battles began when Lee sent multiple assaults against General Porter’s dug-in V Corps on the Union’s right flank. He intended to destroy the V Corps and rout the other 80 percent of the Union Army. Stonewall Jackson was not in place when Lee wanted to attack; however, once he arrived, the Confederate assault of more than 30,000 men led by General Hood’s Texas brigade swept the field in this largest battle in the East.

Although a great victory by any measure, Southern forces failed to follow and destroy the retreating Federals. This decisive Confederate victory convinced McClellan to change his base of operations to the more secure James River. In the sense that this battle saved the Confederate capital, whose fall in 1862 could have ended the war much earlier, this battle ranks as one of the most important of the war.

What to see: There are many markers and a walking trail.

Visitor info: Richmond National Battlefield Park, 6283 West House Rd., Mechanicsville, www.nps.gov/rich

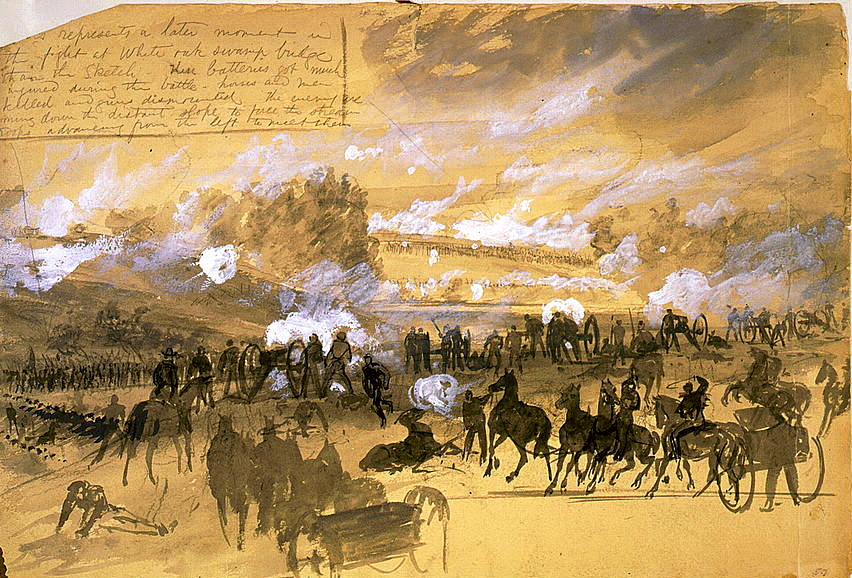

Glendale/White Oak Swamp

June 30, 1862

As Federal forces retreated from just outside Richmond, action took place at Glendale, the fifth of the Seven Days Battle. Lee wanted to trap retreating Federals and crush them. Generals Longstreet and Hill assaulted forces under Generals McCall and Kearny. In the heat of battle, the Confederates seemed to be gaining ground until a bayonet charge made by the 69th Pennsylvania crashed into Longstreet’s men, turning the tide of the battle for the Union, which evaded destruction.

Meanwhile, as fighting at Glendale raged to the south, General Franklin’s Union rear guard engaged Stonewall Jackson’s men in an artillery battle at White Oak Swamp. Jackson’s failure to support his fellow Confederates in a more meaningful way remains controversial today. The conventional interpretation is that Jackson was fatigued and unsure of what he could or should do. But was that true? The historical debate rages on.

What to see: Visitors should start at Malvern Hill Visitor Center in Richmond National Military Park.

Visitor info: Richmond National Military Park, Glendale/Malvern Hill Visitor Center, 8301 Willis Church Rd., inside Glendale National Cemetery, www.nps.gov/rich

Hampton Roads

March 8-9, 1862

The advent of modern naval combat began here, near Fort Monroe and Fort Wool, on March 8, 1862, when Confederate ironclad C.S.S. Virginia, outfitted with 12 guns and a ram, battled five wooden Federal ships with a total of 219 guns, sinking one, grounding another, and nearly finishing off a third. On March 9, the Federal ironclad U.S.S. Monitor, with its innovative swiveling turret design, battled the Virginia to a draw before withdrawing.

What to see: The U.S.S. Monitor Center at the Mariners’ Museum, at 100 Museum Dr. in Newport News, is a worthwhile stop—worth every penny of the $1 admission, https://monitorcenter.org

Visitor info: Markers located in Monitor-Merrimac Overlook Park, 16th St. (Va. 167), Newport News.

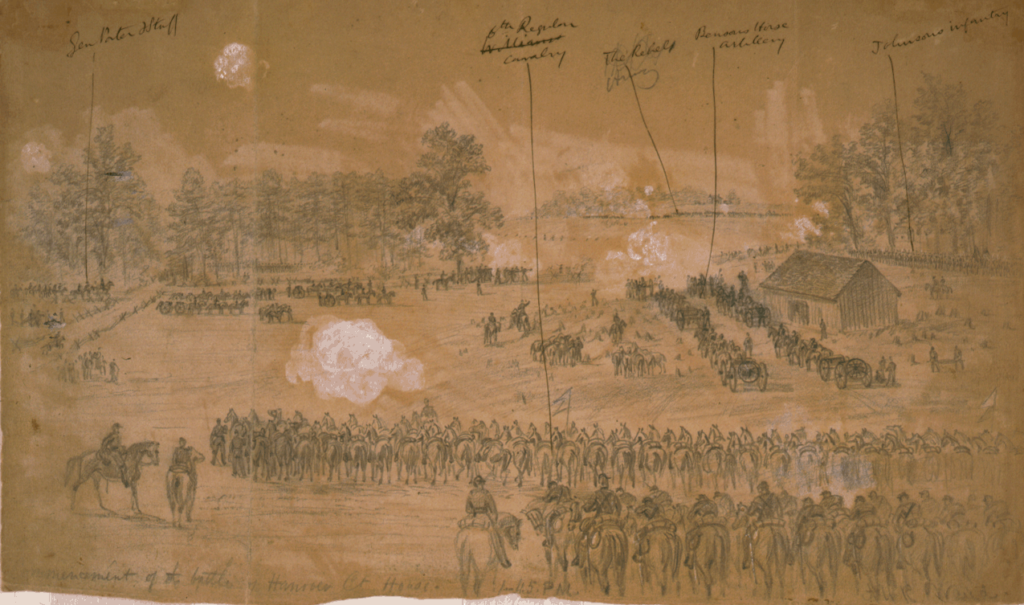

Hanover Court House

May 27, 1862

Union General Porter’s V Corps moved north to protect General McClellan’s right flank, which straddled the Chickahominy River. They aimed to disrupt the railroad line and open Telegraph Road as a route for Union reinforcements coming south from Fredericksburg. Near the colonial-era Hanover Court House, they were confronted by Confederate troops, which they defeated in a fierce battle. The Union reinforcements never arrived, however, because this time, Stonewall Jackson had begun his remarkable Valley Campaign, and the federal government, fearing for the security of Washington, D.C., had ordered them to hold in place in the event they were needed to repel Jackson.

Visitor info: Marker and monument to Confederate soldiers located outside historic Hanover Court House, 13182 Hanover Courthouse Rd. The colonial-era Hanover Tavern is nearby.

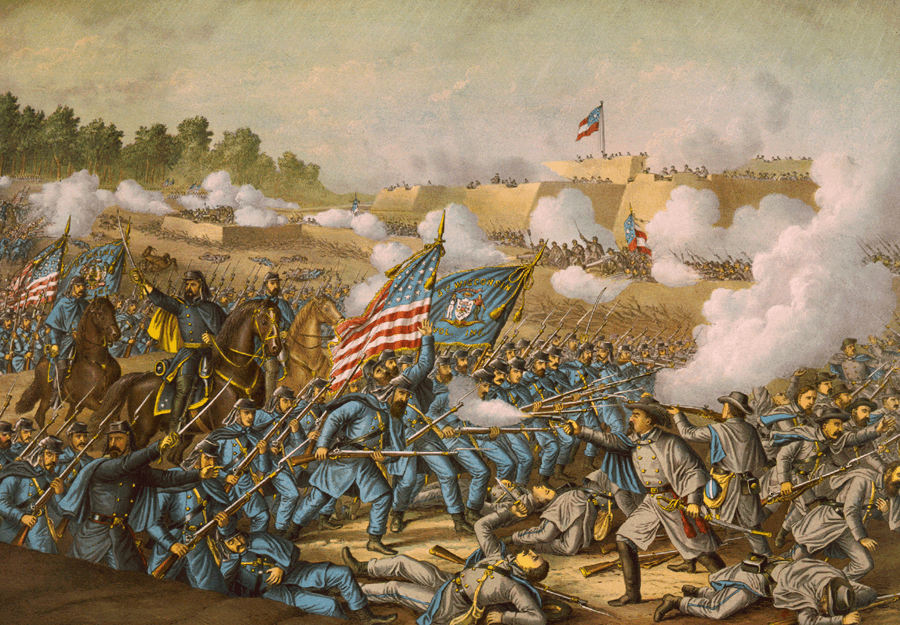

Malvern Hill

July 1, 1862

Despite the hard fighting of the previous days, Lee still hoped to destroy McClellan’s army. This led him to make one of the worst decisions of the war. Believing a coordinated infantry assault could take Malvern Hill if Union artillery were suppressed, he ordered Confederate artillery to bombard the hill. He was unable to bring sufficient fire on the hill to justify attacking, and the Rebels suffered 5,000 casualties. The Federal position was so strong that less than one-third of the Union army saw combat that day. The final battle of the Seven Days Battles was a Confederate disaster not duplicated until Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. That night the Federals slipped away to their new supply base at Berkeley Plantation on the James.

What to see: Today the battlefield is nearly restored to its 1862 appearance, with walking trails and many markers. While the battlefield is open year-round, the Malvern Hill Visitor Center is open in the summer only.

Visitor info: Malvern Hill Visitor Center, 8301 Willis Church Rd., inside Glendale National Cemetery, Richmond National Battlefield Park, www.nps.gov/rich

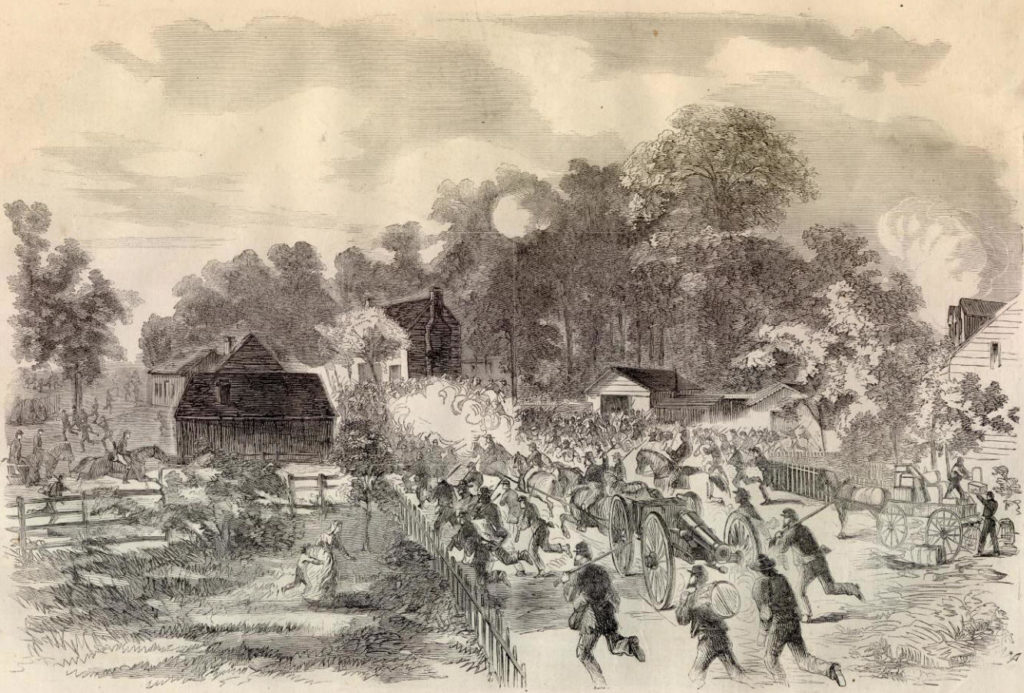

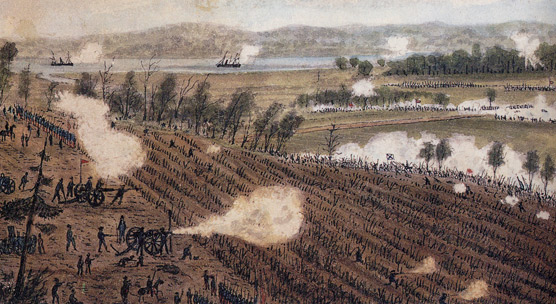

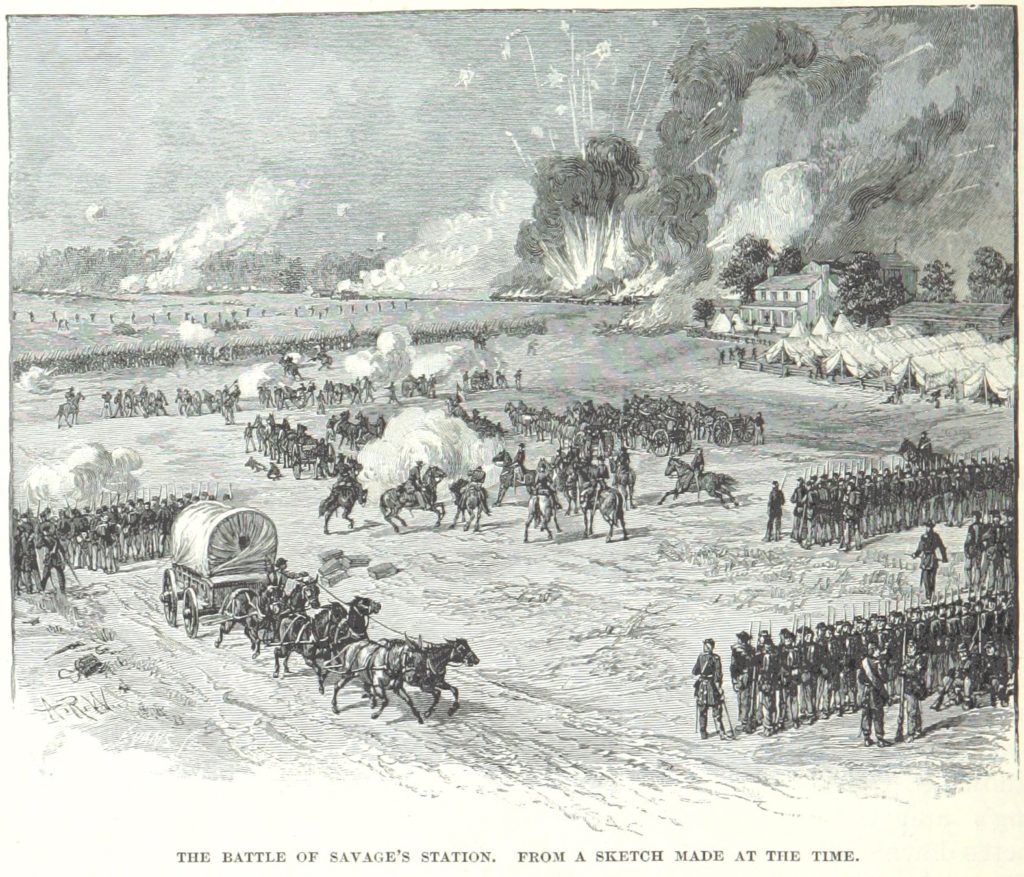

Savage’s Station

June 29, 1862

As the bulk of the Union Army withdrew toward the James River, General Magruder followed, striking the Union rear guard under General Sumner. When Magruder asked him to assist, Stonewall Jackson replied that he had other business to attend to, leading some historians to criticize Jackson and others to speculate that Lee had given him a special role to stay above the fray and then entrap McClellan’s army when the time was right. The day’s inconclusive fighting ended as Union forces continued to withdraw.

Visitor info: Multiple markers located on Meadow Rd. just east of the intersection with Grapevine Rd. in Sandston. The core of the battlefield sits in the I-64 and I-295 interchange. Critical parts of the battlefield are visible on Va. Rte. 156 just beyond Grapevine Bridge.

Seven Pines

May 31-June 1, 1862

With McClellan dangerously close to Richmond, Joe Johnston, general in chief of the Confederate Army, launched disjointed attacks against Federal forces south of the Chickahominy River. Both sides poured more and more troops into the battle, making it the largest in the eastern theater to that point. On the first day of fighting, Union forces were driven back, with both sides suffering heavy casualties. Southern attacks continued on June 1, but to little effect for either side.

Although an important battle in its own right—with around 11,000 men killed or wounded—Seven Pines’s real impact on history comes from the wounding of General Johnston. He was replaced by Robert E. Lee. Soon Lee would plot a massive assault—the Seven Days Battles—that would drive the Federals away from Richmond and, if properly executed, destroy the Union Army.

Visitor info: Multiple interpretive markers line E. Williamsburg Rd., from the intersection with Nagle Ave. West to the intersection with Early Ave. in Sandston. Two other markers located on nearby Casey St.: The first, going east, is just before the intersection with Rodes Ave.; the second, continuing on the road for one-fifth mile, is just before the intersection with Hunters Wood Ln.

Williamsburg

May 5, 1862

As the Confederates retreated from Yorktown, Union General Hooker attacked the Southern rear guard while assaulting Fort Magruder. General Kearny thwarted strong counterattacks by Longstreet, and General Hancock seized unmanned portions of the Confederate left, although Federal forces did not follow up on these gains. The Rebels retreated in the night.

What to see: Williamsburg today has a number of Civil War sites, including Bassett Hall. It’s part of the Williamsburg walking tour featured in a previous BGES blog post and in the National Geographic’s The Civil War, A Travel Guide. Soldiers camped out on the campus of William and Mary and used Wren Chapel as a hospital. If visiting nearby Jamestown Island, ask about the Confederate batteries onsite. In winter, a drive along the Colonial Parkway to Yorktown will reveal Confederate earthworks overlooking the York River. The enhanced earthworks at Yorktown are from this Civil War campaign. There are also multiple battle markers located at the intersection of Hwy. 60 and 5th Ave. in Williamsburg.

In addition, you’ll find the remains of Fort Magruder with markers located at the intersection of Queens Creek Rd. and Penniman Rd. in Williamsburg. There’s also a marker and redoubt in the courtyard of the Fort Magruder Hotel, 6945 Pocahontas Trail, Williamsburg, 757-220-2250. Finally, a walking park at the end of Quarterpath Road preserves two of the Confederate Redoubts 1 & 2.

Yorktown

April 5-May 4, 1862

With the aim of taking Richmond, General McClellan moved from Fort Monroe and encountered a small Confederate force at Yorktown. Wrongly, he believed that the Southern defenses and manpower were stronger than they really were. He dug in, with siege guns and heavy fortifications.

On April 16, McClellan’s troops staged a successful attack at Dam 1, but the wary Union general did not commit sufficient forcese to exploit his gains. Instead, McClellan prepared for a heavy full assault on May 4. The Rebels, however, had other plans. They evacuated in the dark, late on May 3.

Although Yorktown is most famous as the field where the Revolutionary War was won, most of the fortifications extant today were shaped by this Civil War battle. While in the area, don’t miss Lee Hall, which was Generals Magruder’s and Johnston’s headquarters, or Edgeview Plantation.

Visitor info: Yorktown Battlefield Visitor Center, 1000 Colonial Pkwy., Yorktown, www.nps.gov/york

Excerpted from National Geographic’s The Civil War, A Travel Guide

You must be logged in to post a comment.