The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History

Edited by Alan Nolan and Gary Gallagher (Indiana University Press, 2000); 231 pages

Twenty years ago, I picked up this book and read it. It was less than a year after 9/11, and knowing the dust-up between Nolan and Lee defenders after Alan’s controversial book Lee Considered in 1991, I was expecting a food fight since Gallagher was a leading Lee defender. I do not remember what I thought of the book at the time—nothing much one way or the other. But, 20 years later and in the wake of the violence that has destroyed so much of our Civil War iconography and leading names, this title took on a new meaning. It proved to be an excellent conversation starter.

Twenty years ago, I picked up this book and read it. It was less than a year after 9/11, and knowing the dust-up between Nolan and Lee defenders after Alan’s controversial book Lee Considered in 1991, I was expecting a food fight since Gallagher was a leading Lee defender. I do not remember what I thought of the book at the time—nothing much one way or the other. But, 20 years later and in the wake of the violence that has destroyed so much of our Civil War iconography and leading names, this title took on a new meaning. It proved to be an excellent conversation starter.

The late Alan Nolan was my friend, an early supporter of the BGES. He and his wife, Jane, joined us on many tours, and he and I shared ideas long before BGES was ever started. An Indianapolis lawyer of some reputation, Alan’s book on Lee read as a legal brief and contained a lawyer’s logic that indicted Lee in a surgical manner similar to Thomas Connelly’s The Marble Man. Both these books and Elizabeth Pryor’s Reading the Man damaged the pedestal Lee was placed on. Understandably, it aroused much anger and resurrected credible and vociferous defenses such as Charles Roland’s Reflections on Lee, A Historian’s Assessment, released in 2003. Lee was at the APEX of Lost Cause mythology and worth another reading.

This book was an opportunity to amplify the points that Nolan had dumped on Lee and, while not published in Gallagher’s typical fashion (through the UNC Press that hired him as their Civil War America editor and which produced numerous books including a long series of campaign essay books), the project was accepted by Nolan’s home press at Indiana University. Gallagher brought the gravitas of the Civil War community and his wide-ranging network of protégés and contacts to the effort. In addition to Alan and Gary, familiar names such as Keith Bohannon, Peter Carmichael, Jeff Wert, Lesley Gordon, Brooks Simpson, Charles Holden, and Lloyd Hunter all contributed essays—each from 10 to 20 pages plus endnotes. The product is a cogent and rapid passage through a subject that could have taken 100 or more essays and not come near exhausting the subject. Gallagher introduces the collection, but Nolan gets the first chapter on the “Analogy of a Myth.” This is clearly Alan’s idea and book.

The book is valuable because it is a fair and unbiased look at how the South emerged from and dealt with the Civil War. It is strong on facts but biased in the interpretation of those facts and their meaning. Ironically, the last essay by Lloyd Hunter on The Immortal Confederacy, Another Look at Lost Cause Religion is illustrative of the problem with the presentation of the book. The series overstates the apologetic and thus propaganda intention of The Lost Cause. In the briefest of terms, the myth is the South’s dependence on a rationalization of why they lost—in short, a justified revolt supported by a unified section of the country against a dominating central government oppressing a morally superior and God-fearing section that merely wanted to maintain their constitutional rights and which seceded only in the face of intolerable provocations that threatened their independence. The southern leadership was vastly superior, and its greatest general, Robert E. Lee, was only defeated by a clumsy and resource-rich vulgarian, U.S. Grant, who overwhelmed the noble southern cavaliers whose values were morally superior but which in the end were unable to overcome the brute force of the invading northerners.

The meaning, though, I believe is deeper than that, and this review by definition must limit itself to creating a further forum for reflection and discussion.

I believe the first issue is, Why would a book like this be necessary? In evaluating the logic of the Lost Cause proponents, the historians not just here but over the century and a half that this “Myth” has existed have missed, I believe, the essential element. I realize that I risk being tarred as a Lost Cause apologist, but must say that every person has intrinsic value and no person wants to live carrying the yolk of guilt for actions and attitudes from previous centuries. For that matter, no peoples (plural added) can live with a dual standard in explaining the era in which they lived. Missing from this series is any context about American values in the 19th century. Additionally, the behaviors of the survivors of this unarguably cataclysmic event must also be put into context.

Nineteenth-century America was, by our standards, a racist, paternalistic society rent asunder by different means of labor suited to the type of work to be performed. With few exceptions, the presence and concern for the capabilities or rights of people of color were not important. Prosperity and free labor clashed with slave labor on multiple fronts. The war occurred because the South believed that its “Peculiar Institution” was endangered by further legislation and a hostile attitude from parties dedicated to the limitation of and eventual extinction of slavery. The right to live in peace was disputed in a war that eventually killed more than 800,000 people and freed 10,000,000 blacks—not because it was right, but because the U.S. President felt compelled to open Pandora’s box as a war strategy to keep interlopers from Europe from meddling in the American conflict.

The ending of the war created a gaping wound that had to be closed to continue onward, and white America did that rather rapidly. In less than 20 years, those same veterans had created a Gilded Age that escalated American exceptionalism and prosperity to world power status. To achieve that, the Old South and New South had to find a common cause with each other and their white counterparts in the North. They largely did that leaving the dirty laundry of emancipation and assimilation for another time. In less than 30 years, they would create an environment in which Plessey versus Ferguson would create a precedent that lasted for more than 50 years—Separate but Equal affected men, women, whites, blacks, and reds. All were legally segregated in a values-based environment that reflected social norms. Leadership across the country and at the highest levels embraced that norm, tolerating behavior that has no place in a civilized society (keeping in mind the purges of the recently constituted USSR and Nazi Germany were less than a generation in the future).

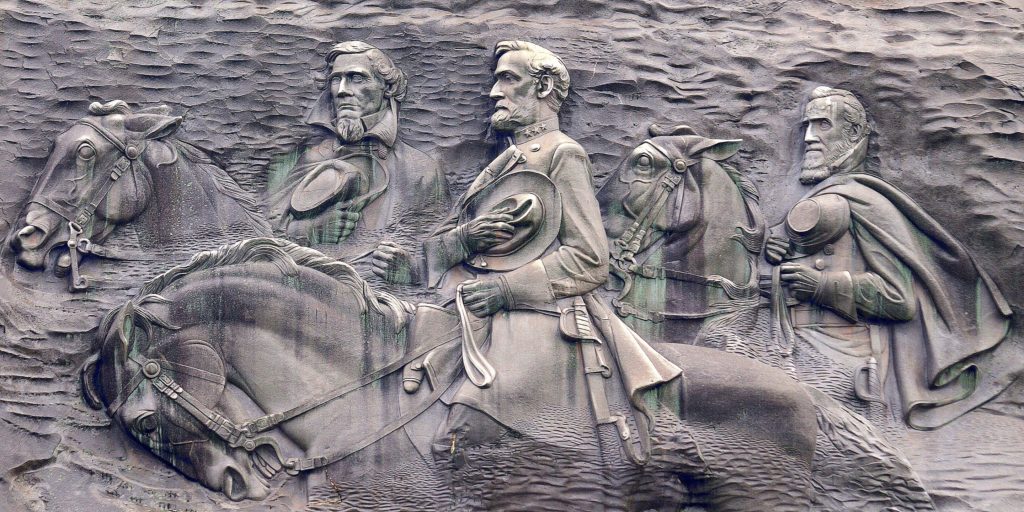

Within the framework of the Lost Cause, southern pride and manhood was restored. It was essential if successful and productive veterans were to move ahead and return to their place in a working and thriving society. Indeed, the entire country engaged in efforts that restored society as the dominant white race wanted it. Racism was a constant in America that was hardly disrupted until Brown versus the Topeka Board of Education. Busing for Racial balance and integration was last imposed in Boston in the 1980s—long after it had been imposed on the South. Why is this important? Well, current scholarship and social justice warriors have backdated the events of 90 to 157 years ago to justify dismantling a significant tool of reunification that was accepted across the United States and to ascribe to it a dark and more hateful purpose than was intended or practical. Of course, southern women elevated their husbands, sons, and fathers. Yes, they memorialized them and took care of widows and orphans; yes, society leaders reassumed leadership roles once the punitive necessities of Radical Reconstruction were played out. So did the Northern widows, wives, parents, daughters, sons, and so forth. For every southern monument, there was a northern monument; for every southern graveyard, there was a national cemetery. And when southerners created Memorial Day, it later assumed national significance, and all soldiers of the Civil War and later wars were honored.

The Lost Cause is presented and held up as some cancer that needs to be expunged from our memory. It is represented as the Great Lie. Further, it assumes a greater prominence in modern-day discussions than it had in the 20th century. That so many historians and writers of and about the period have assimilated the southern rationale for losing their bid for an independent nation in their analysis may explain why there were so few books of the Connelly, Nolan, and Pryor genre (although more are coming out, as the dominate historiographic theme evolving out of the Ivy League is “Memory”). It seems to me that the great challenge has been to get people riled up about an event and an explanation that was uniquely white and which did not have as much to do with the greater national question of Emancipation and assimilation than it did with the immediate need to mend the fences and move ahead.

I get it. The problems and consequences of the Civil War still stick in some people’s throats. After every war, there is always a group of vengeance warriors, people who believe that a price should be extracted for the death and destruction that has been rendered—look at the post-Lincoln presidency of Andrew Johnson. However, Abraham Lincoln understood it better than most, and in his Second Inaugural Address, he adopted a conciliatory policy that would “Bind up the Nation’s Wounds, care for those who had born the battle and for their widows and orphans.” That new birth of freedom was not and could not be a turnkey event. As we have painfully seen, it took more than 100 years to end Reconstruction and move ahead with real Civil Rights legislation. But Lincoln understood the need to grieve, and thus there were no planned Nuremberg-style trials, no mass incarcerations, and no wholesale executions—revenge was not in Lincoln’s DNA. Instead, he set a blueprint for the healing that would follow. Sadly, he died too soon, and it took men like U.S. Grant to see that his intention was carried out. Lee survived to build a great institution of higher learning: Washington and Lee; and southern soldiers served again in the U.S. Army in future wars.

Alan Nolan really believed Lee betrayed the nation, and many other critics of the Confederacy and the South believed that Davis, Lee, and the entire South should have been punished for what they did to the country. I hear it today from members of the BGES and the general public. Many academics believe the South was 100% wrong, and its leaders should have paid a heavy price. Yet some Confederates had their rights of citizenship restored as late as 1975. Many soundbite critics have adopted the same attitude about a very complex passage in our national maturation. I found in rereading the essays that they were intrinsically biased and they were—how can nine individuals summarize a larger construct without crawling down many rabbit holes? More than that, how can they respect the judgment of the people who lived with those leaders of America from so many years ago without making an objective analysis of the society as a whole and which moved ahead as a whole? If one’s society and way of life is turned 180 degrees in a matter of a couple of years, how would people today respond? The Lost Cause was about restoring self-respect, rationalizing something that to us seems intuitively obvious but which was not forced upon them until it was upon them.

This book is valuable not as a tool of indoctrination. Indeed, think of where we were when these essays were being written. The Twin Towers still stood in New York, Bill Clinton was ending his presidency, and the Y2K phenomenon was proving to be much ado about nothing. If you have made up your mind or are a “Nothing but the facts, Ma’am” kind of person, this will not arouse you. If you believe the South should have been punished and still believe it, this will give you ammunition without context about the rest of the country. If you are hard into Jim Crow and monument construction as an insidious contrived measure to intimidate and control blacks, this will give you the explanation to rationalize a general degradation of the South and its ill-fated rebellion.

On the other hand, if you can project yourself into the times, challenges, problems, and opportunities presented to a vibrant section of a century-old country with 250 previous years of evolving culture, then perhaps you will see the rationale behind the myth of the Lost Cause. Yes, people were making stuff up. They do today as well. Were there misrepresentations of facts? Yes, there are today as well. And have people been escalated and or blamed for their decisions? Yes, and they are today as well.

For now, this book should give you plenty to think about—not just for the period from 1866 to 2000, but now and for the future. Was the destruction and response to the myth of the Lost Cause from 2020 through today appropriate?

—Len Riedel

You must be logged in to post a comment.