Storm Over the Land: A Profile of the Civil War

By Carl Sandburg (Mariner Books, 2000; originally published 1939)

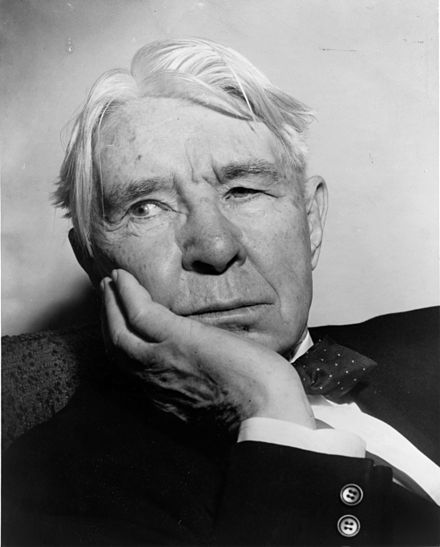

In our current assault on American history, it is often useful to reflect back on how war was treated in our past. Pulitzer Prize–winning poet and historian Carl Sandburg presents us with one such prism with his turn to history after winning a Pulitzer Prize for literature at the close of World War 1.

Sandburg, an Illinois native, had already written the first part of his magisterial study of Abraham Lincoln, and the Depression was in full impact in both America and worldwide. Richmond-based historian Douglas Southall Freeman had won the Pulitzer for his four-volume biography of Robert E. Lee and was now working on the companion study of Lee’s leadership that found its way into many World War II officers’ knapsacks—Lee’s Lieutenants. Later, he would write a multi-volume biography of George Washington. Sandburg was finishing the second part of his Lincoln study, “The War Years,” when this companion volume came out.

Freeman was the son of a Confederate veteran, and veterans of each side were dying off rapidly. The year before, President Franklin Roosevelt had dedicated the Peace Light Memorial at Gettysburg, and the final 75th reunion of veterans had been held at Gettysburg. The world was again teetering on the brink of war—Germany was expanding, and Poland would soon be invaded. Freeman later admitted that part of his inspiration for Lee was to offer the nation in despair a shining beacon of dignity under extraordinarily adverse circumstances to show that ’30s America could and would survive the Depression. As Sandburg had completed the “Prairie Years” portion of the Lincoln biography in 1926, I doubt this volume of the second portion, “The War Years,” released in 1939, was crafted under the same inspiration. I suspect the Illinois connection was more relative to Sandburg.

So why this book? The introduction notes that substantial portions of the narrative were previously published in the Lincoln biography. Contemporary criticism of the Lincoln biography is familiar. Were Winston Groom or Shelby Foote still alive, they would recognize the criticism that “Sandburg wrote romanticized literature that failed the rigid standards of historical research.” Groom’s response to such criticism was that historical writing need not be aggressively footnoted except for the academics who wanted to be able to nitpick various interpretative conclusions. There is much to be said for this point.

So why this book? The introduction notes that substantial portions of the narrative were previously published in the Lincoln biography. Contemporary criticism of the Lincoln biography is familiar. Were Winston Groom or Shelby Foote still alive, they would recognize the criticism that “Sandburg wrote romanticized literature that failed the rigid standards of historical research.” Groom’s response to such criticism was that historical writing need not be aggressively footnoted except for the academics who wanted to be able to nitpick various interpretative conclusions. There is much to be said for this point.

I suspect Sandburg likely wrote this book to prop up acceptance of the rather narrow focus of the Lincoln biography and perhaps in response to some criticism of the work. With a very strong sense of regional, yes confederate, identity still present within the nation, a survey work and reflection on the 75th Commemoration of the war was low-hanging fruit. Still, Sandburg, who had witnessed the impact of the First World War and had witnessed, with the rest of the world, the storm clouds on the horizon in the Pacific and Europe was, stated, “Perhaps the volume can be of use in a time of storm to those inexorably aware ‘time is short.'” That the book was reprinted in 1942 suggests that many people turned to his calming analysis to reconcile that America was again “at war.”

The book Sandburg wrote is pleasant reading. It is a survey of the war that whisks rapidly through events that in the 82 years since have been sliced, diced, and carefully examined by professional historians and dedicated historical curmudgeons who would parse every line. With that in mind, it is important to fall back to the primary criticism and treat this work as a work of literature and in that it is both utilitarian and rewarding. The book does not delve into detail beyond the human insight that no doubt interested a man of letters. Indeed, Sandburg notes a comprehensive work would require ten times the 384 pages penned here. Having read the voluminous works of Bruce Catton and Shelby Foote, I concur that Sandburg is clearly right.

The book Sandburg wrote is pleasant reading. It is a survey of the war that whisks rapidly through events that in the 82 years since have been sliced, diced, and carefully examined by professional historians and dedicated historical curmudgeons who would parse every line. With that in mind, it is important to fall back to the primary criticism and treat this work as a work of literature and in that it is both utilitarian and rewarding. The book does not delve into detail beyond the human insight that no doubt interested a man of letters. Indeed, Sandburg notes a comprehensive work would require ten times the 384 pages penned here. Having read the voluminous works of Bruce Catton and Shelby Foote, I concur that Sandburg is clearly right.

The reality of what this book was is evident as the book narrative expands dramatically and in detail as he addresses important elements of the Lincoln presidency—the Emancipation Proclamation, the 1864 election, and the funeral of Lincoln. That poetic license is understandable and a wonderful sop to folks who have not had the pleasure of reading the five-volume Lincoln biography Sandburg had previously published.

Because this is not an original work but rather an edited cut and paste from other works, I give it just three stars—minus two for that style, but a strong plus-three for the skill and sensitivity that comes from accepting the limitations of the work and still presenting a very readable and cogent narrative that teaches all. To the “would be” writer, he admonishes you to “Write till you are ashamed of yourself and then cut it down next to nothing so the reader may hope beforehand he is not wasting his time.” Then perhaps reflecting the attitude of the ’30s society, he closes by quoting a post-war Robert E. Lee advising a visiting mother about how to raise her child: “Teach him he must deny himself.”

—Len Riedel, BGES Executive Director

Photos: Public Domain