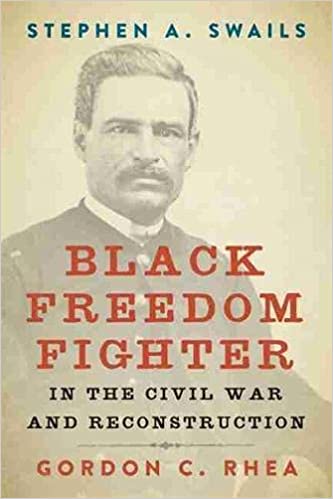

Stephen A. Swails, Black Freedom Fighter in the Civil War and Reconstruction

By Gordon C. Rhea (LSU Press, forthcoming November 2021)

Gordon Rhea will be leading the BGES tour “The 1864 Overland Campaign Part 1: Grant versus Lee,” on October 18-23, 2021.

There are two related videos on BGES YouTube channels that are worth a look: Gordon Rhea’s Conversation with Len Riedel about his book; and Gordon Rhea’s discussion with Len Riedel about Stephen Swails, Black Freedom Fighter.

I have known Gordon Rhea for some 27 years, and he has become a close friend. We disagree politically but have always maintained a cordial and constructive relationship, so it is with no small amount of consideration that I decided to review his new book. Generally, folks with a warm relationship should avoid such appearances of partiality, and I wanted to acknowledge the relationship upfront.

Rhea is well-known for his definitive five-volume treatment of the 1864 Overland Campaign, which has won numerous awards and cemented his relationship with his publisher, LSU Press. He also has written a heart-rending biography, Carrying the Flag, The Story of Private Charles Whilden: The Story of the Confederacy’s Most Unlikely Hero. One wonders where the lawyer from Mount Pleasant finds the time? Yet, everyone is well researched and significant. His latest book is no different—and yet, it has a meaning that reaches out and touches the souls of all who openly consider the story and its implications in the 21st century.

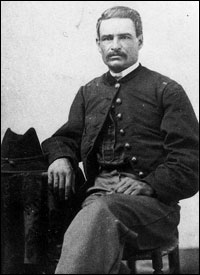

Swails was a free man of color who enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts. This amalgamation of freedmen and former slaves was a milestone in the history of the Civil War, and while not the first black regiment to serve or fight, it certainly was the most storied, immortalized by the movie Glory. Since the war, a number of books detail the key players in the regiment, but who today, honestly, knows who Stephen Swails is? Well, I’ll tell you.

The light-complected Swails rose to non-commissioned officer ranks and participated in the storied charge at Battery Wagner in July 1863, as well as in most other events in the regiment’s history. But he is legendary for having fought the system to become the first commissioned officer of color in the United States military, and as 2nd lieutenant, he served with distinction until mustered out shortly after the war ended. In and of itself, that might be cause for a biography, but that is merely the entrée.

Rhea has written a powerful biography that is rather interesting as far as the Civil War is concerned. That said, it is essential and sobering as it relates to Swails’ postwar experiences. You see, he settled in South Carolina, where he became a central figure in reconstruction politics, first as an agent of the Freedman’s Bureau, and then as a citizen of Kingstree, South Carolina. Swails served in a variety of elected and leadership positions as South Carolina reconstructed, and then he turned to “Redemption Politics” under Wade Hampton and others, which eventually led to the codification of Jim Crow and “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman’s segregationist politics at the turn of the 20th century. This era was marked notably by Plessey versus Ferguson and the “Separate but Equal” doctrine that governed the country for the first 55 years of the 20th century.

Swails was a war hero, but he also was considered a carpetbagger—a term of derision and contempt in the South. Despite his leadership in the state and his community, he was marginalized, terrorized, and eventually expelled from the state. He was compelled to take a clerkship in Washington, where he was stalked and eventually fired from his position due to the influence of the South Carolina senators.

This is not the first account of the post-Civil War era in South Carolina and elsewhere that I have read, and the evidence is pretty clear that as a means of social control, newly minted citizens of color were systematically denied their new-found freedoms, especially voting rights. That Congressman James Clyburn from South Carolina, the most powerful man of color in the United States Congress, would write a blurb on it merely heightens the importance the work has to understand much of the underlying tensions over voting rights today.

What does concern me, and it is mitigated by some very legitimate counter-arguments, is that Rhea does not contextualize the social chaos of the time. In a society whose entire way of interacting, whose wealth and system of labor have been turned upside-down in a matter of a decade, the desire to restore some means of control and return to normalcy is understandable. Resorting to violence in the presence of a new reality in which hundreds of thousands of Southern men have been removed from the voter rolls and replaced by hundreds of thousands of formerly voiceless and now constitutionally empowered men of color is a huge change that history has told us is generationally difficult to accept. Indeed, more than 150 years later, we are still dealing with the ramifications.

Conversely, the well-made counter-argument is the one of teaching someone to swim by tossing them in the deep water, knowing they will sink or swim, and most will swim out of necessity. People who age by the day cannot wait, and, indeed, should not wait to exercise natural rights that were denied for a hundred years or more. And so there we have the fertile middle ground that has inflamed and challenged us since Appomattox. It has many permutations.

Rhea’s book is essential not because Swails was a part of the 54th Massachusetts, but because it is a flesh-and-blood documentary and analysis of the daily struggle for equality that was Reconstruction. It is the “So What” of the purpose for the Civil War, and it is the intractable responsibility of subsequent generations to redeem the blood of more than 800,000 men and the valor of more than 200,000 men of color who fought for Union and Freedom. The book does not get lost in the horse latitudes with minutia or philosophical crusades for equal rights. It is about the postwar experiences of a man of great leadership potential repressed and denied the basic civil rights that he fought and earned.

We spend a great deal of time focused on the shooting war and little on the real consequences of this war and its aftermath on America and its promise. Most survey courses in American history run from founding to 1865 and then 1865 to the present. That is a shame because it highlights the Civil War as the singular and perhaps most critical event in American history while denying the impact of more than 100 years of narratives, rationalizations, and celebrations of the veterans of war and their commemorative efforts that stretched throughout their lives. Yet here is the story of an American military veteran mustered out after service to his country and his country’s response to him and his service in the ensuing 40 years. It is powerful.

I highly recommend this book and invite you to hear my interview with Gordon that will be on the BGES YouTube page around the time we release this review. The book will be released in November 2021. If you are a serious student of the Civil War, you should not miss reading it.

Len Riedel

You must be logged in to post a comment.