The art of bringing news of the battle, words and pictures intertwined, began with the very first war correspondents and special artists during the mid-19th century. Acclaimed war illustrators such as Alfred Waud and painter Winslow Homer captured the public’s ravenous attention for news of the war, as did the early photojournalists Timothy O’Sullivan and Andrew Gardner, who photographed the vanquished dead in the trenches. Even well-known Lincoln portraitist, Mathew Brady, established a battlefield studio to sell cheap cartes de visite for soldiers to send home.

One interesting artist was James E. Taylor, an itinerant jack of all trades who was born in 1839 and only sporadically educated. Prior to the onset of the Civil War, his brush and pencil caught the big and small moments at the trial and execution of John Brown at Harpers Ferry. But perhaps what he’s most famous for is his coverage of the Gen. Philip Sheridan campaign in the Shenandoah Valley, which began in 1864. His sketchbook was published in 1989 by Western Reserve Historical Society and it sold like gangbusters. Today, it’s out of print, and the rare copies that can be found sell for more than several hundred dollars.

Enter Dana MacBean, a photographer, cartographer, researcher, and historian who has spent 20 years researching the James E. Taylor Sketchbook. He has retraced Taylor’s journey through the Shenandoah Valley to create a series of “then and now” images, and drafted a manuscript that places them alongside one another with interpretation. We’ve asked Mr. MacBean to provide insight into this extraordinary sketchbook and its artist, James E. Taylor. And here’s the fun part: You’ll find some samples below.

BGES Blog: Please describe what the sketchbook is today.

DM: James E. Taylor’s “With Sheridan Up the Shenandoah Valley – Leaves from a Special Artist, Sketchbook and Diary” is a visual and narrative source of information and insights into the Civil War during 1864. Hired by the publisher Frank Leslie in August of that year, Taylor was instructed to follow the Federal troops in the Shenandoah Valley and draw in detail everything he viewed with his sketches, which would then be translated into the engravings found in Leslie’s Illustrated magazine. What gives Taylor’s huge diary its greatest interest, aside from the accuracy of the historical scenes, is his own personal story interwoven throughout and recorded in great detail. As much as he was an eyewitness to many of the extraordinary events that enveloped the Shenandoah region in 1864, including the battles of Winchester, Fishers Hill, Toms Brook, and Cedar Creek, I believe that the numerous human-interest stories involving the civilians and the impact the war made on their lives has the most appeal to the reader.

BGES Blog: Can you speak to what sparked your interest in this research on Taylor and his manuscript?

DM: When searching out the contemporary equivalents of Taylor’s sketches, the reader is generally presented with two conflicting emotions. Often, the locale is found virtually unchanged from Taylor’s time and the sketch literally comes alive. Be it the scene of a great battle or a village smithy, the sweep of an army on the march or a farmer plowing his fields, Taylor’s sketches turn modern-day views into moments of near-spiritual awakening, allowing us to touch in a very real sense American’s past.

However, just as often, much of that exhilaration is lost when a site is found destroyed, replaced by strip malls, highways, and anonymous architecture. Unchecked development is sweeping away much of American’s historic landscape, especially the Shenandoah Valley, which has become a prime target. Taylor’s sketchbook now serves as a barometer, both for what we still have and for what we have lost. Additionally, Taylor was as much a storyteller as he was an artist, and he would often foreshortened the depth of field or compress the scene in order for the illustration to fit the page of the newspaper or periodical and for the picture to have more impact. It is therefore sometimes difficult to locate his artist’s point of view.

Civil War historian and author Pat Brennan and I envisioned a “then and now” approach to a possible companion book to the Sketchbook. He pointed out that it’s important for the viewer to get into “Taylor’s Mind Eye” when comparing the drawing with the actual scene as it is today. This presentation style was quite popular in the past and still enjoyed today. Civil War photography expert William Frassanito released photo-studies that incorporated the “then and now” approach, which remain in print today.

Thanks to the support and recommendation from a number of historians, including Len Riedel of the Blue and Gray Society and former National Park Service author and historian Ed Bearrs, Pat and I produced a companion piece to the events described in the book. I developed the maps and provided the photographs from the artist point of view. Today there are 71 maps divided into the four regions of Maryland, West Virginia, and Lower and Upper Shenandoah Valley. Approximately 360 photographs have been taken.

BGES Blog: Why is James E. Taylor’s sketchbook so important?

DM: I believe James E. Taylor was born to be an artist. I think he knew from a very early age that his career choice would be in the field of the visual arts, which would ultimately gain him national recognition. One of the best examples of author-artist compilation efforts can be found in the diary memoirs of Pvt. Ezra Ripple, “Dancing along the Deadline,” in which Taylor’s drawings depict the events surrounding the life of a prisoner of war in Andersonville and the Florence Stockade. Taylor’s signature style is to clearly show emotions in the faces of his subject even at times when he’s drawing from “non-observed reality.” He was an artist who was adept at translating those emotions on paper with the realism sought after by the general public.

Frank Leslie quickly realized that James E. Taylor was a gifted news-artist. His ability to capture a scene, coupled with an uncanny attention to detail, was extraordinary. He thought he was simply supplying his employer with visual material for newspapers reports. But in the process, he left an unparalleled illustrated record of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley at the height of the Civil War.

The Taylor Sketchbook and journal is the property of the Western Reserves Historical Society in Cleveland, Ohio, which acquired the collection of steel industry executive William Palmer. He amassed one of the most extensive personal collections of the Civil War. But it wasn’t until years later that the staff was able to open and examine the many crates of the collection. In one of those crates was James E. Taylor’s “With Sheridan Up the Shenandoah Valley – Leaves from a Special Artist, Sketchbook and Diary.” The collection was cataloged and stored away, forgotten until almost a hundred years later in 1989 and 1991, when Robert Younger of Morningside Publication of Dayton, Ohio, finally published the diary. The sales of the book surpassed all expectations, with both publications quickly selling out.

Below are some examples of the “Taylor Sketchbook” juxtaposed with MacBean’s photos and excerpts from his draft manuscript.

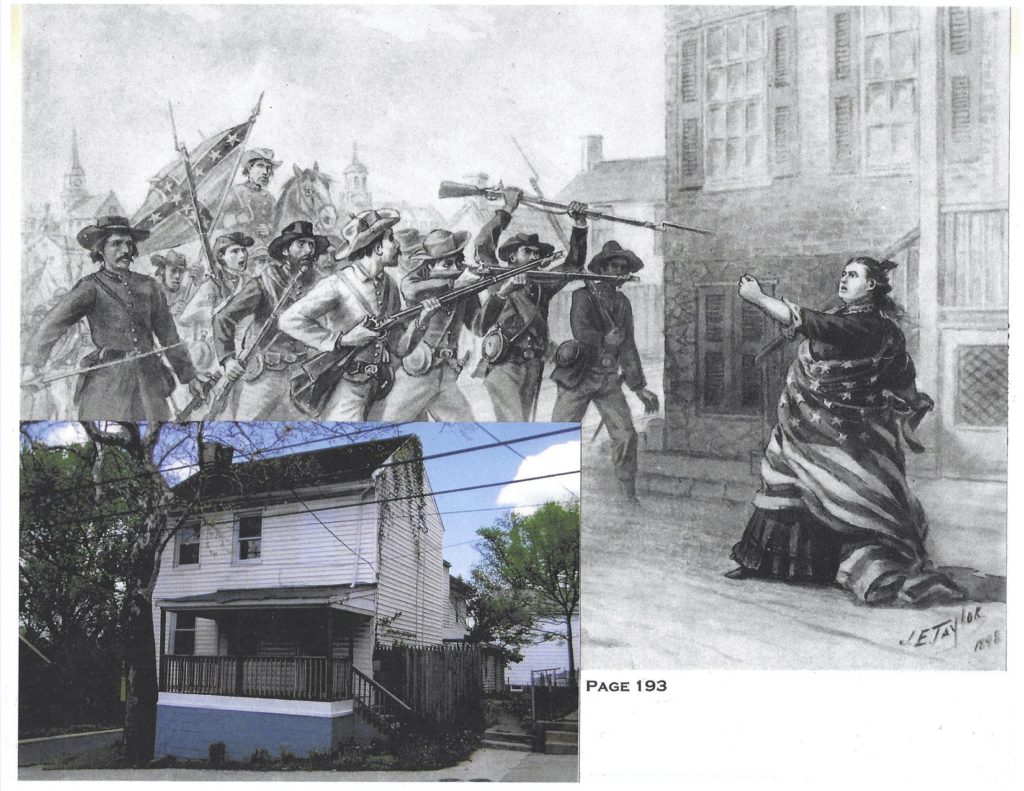

The Stars and Stripes, Martinsburg On the way east out of Martinsburg, Taylor made a quick study of Major General Robert Patterson’s early war headquarters, the Henry Small residence on Queen St. But of greater interest to the artist was Henry Miller’s home on a hill east of Tuscarora Creek. There, on July 3, 1864, Miller’s wife Mary had wrapped herself in the Stars and Stripes as she taunted a column of marauding Confederates. After capturing a fine study of the house, Taylor composed a small portrait of the brave lady. Later he would create a stirring drawing of the confrontation based on his interview with her.

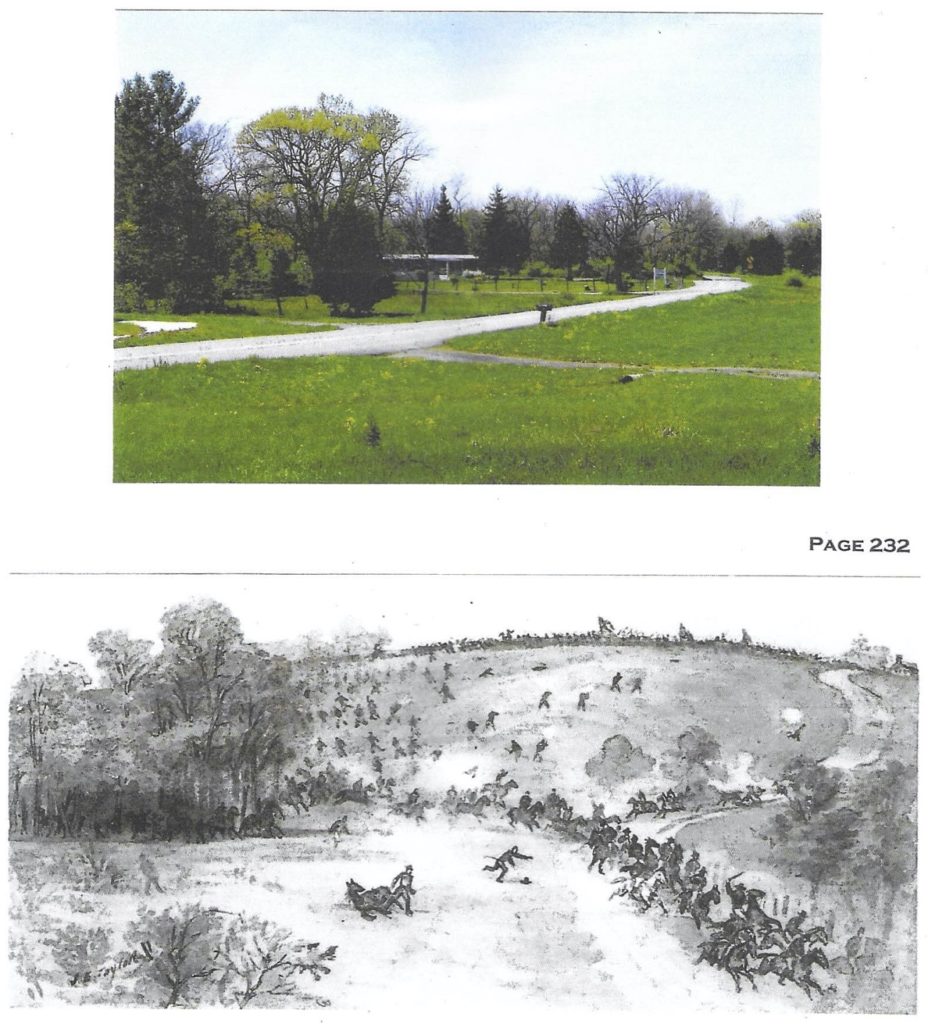

Caught between the lines, Summit Point After a half hour, Taylor decided to inspect the latter’s position, arriving just in time to hear a swelling of picket fire followed by the terrifying Rebel Yell. A bristling Confederate infantry line swarmed toward McIntosh’s troopers and the horsemen—Taylor included—quickly gave way under a hail of riflery. As the startled artist galloped east, a nearby cavalryman took an enemy minie ball and fell from his horse, uttering a death cry Taylor would never forget.

Caught between the lines, Summit Point After a half hour, Taylor decided to inspect the latter’s position, arriving just in time to hear a swelling of picket fire followed by the terrifying Rebel Yell. A bristling Confederate infantry line swarmed toward McIntosh’s troopers and the horsemen—Taylor included—quickly gave way under a hail of riflery. As the startled artist galloped east, a nearby cavalryman took an enemy minie ball and fell from his horse, uttering a death cry Taylor would never forget.

You must be logged in to post a comment.