A native son of Virginia, born in Richmond “right in the shadow of Jeb Stuart,” Art Taylor was drawn to Confederate lore from an early age. “The Seven Days’ Battle culminated at my ancestor Watt’s house, with third grandmother Sally Watt being carried out as battle began,” he says. A former V-Dot employee, he’s a life member and serving his fifth term as president of Hanover County Historical Society. It’s clearly in his blood.

So when Teresa Stevenson, “founder” of the Friends of North Anna, called him in the late 1990s about getting involved with the preservation of North Anna Battlefield, he was all in.

Much of the original Lake Anna battlefield lands were gone or threatened, but a tiny parcel of the battlefield had been preserved in the 1980s, when Martin Marietta Materials, the company that owns a quarry located on part of the original battlefield, donated a small number of acres. North Anna Battlefield Park was opened in 1996 with that small bit of land, but it wasn’t enough to truly preserve the site.

Taylor took up the preservation fight in 2007, working with Martin Marietta to donate additional acreage.

“They were initially talking about a mere 20 acres or so,” says Taylor. “I became a committee of one to ‘get more land’ for the North Anna Battlefield Park preservation and expansion. I sniffed around and found that all the entities that were in support of the idea had been isolated. By uniting all the stakeholders, we increased our negotiating power. We wound up getting an additional 90 acres.”

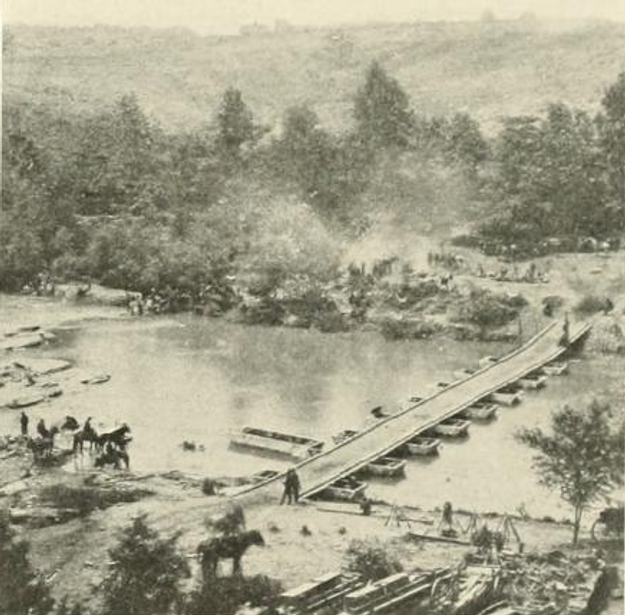

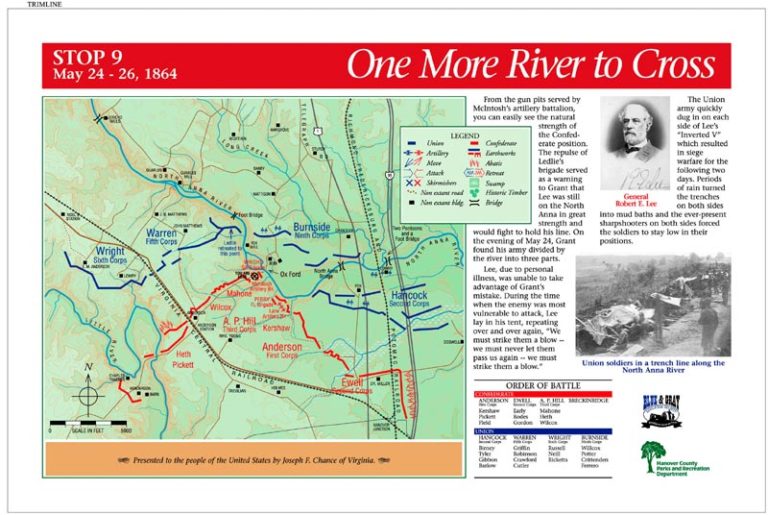

The Battle of North Anna, which took place between May 21 and 26, 1864, between Fredericksburg and Richmond, was part of U.S. Grant’s Overland Campaign against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. Three days after the bloody Battle of Spotsylvania, more than 150,000 soldiers faced off in a small number of engagements along the small, unnavigable North Anna River. Unlike the slaughter of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, the Battle of North Anna seemed “a matter of brains between the generals, than brawn between the men,” recalled William Meade Dame of the Richmond Howitzers. “Some sharp fighting, on points right and left, but that was all!”

The battle is best known for Lee’s cunning inverted V or “hog snout” defense, which threatened to split Grant’s army into three parts—but didn’t. Two days of skirmishing resulted in an inconclusive battle, with both sides wrongly believing the other had lost its morale and willingness to fight. Grant moved downstream, and the two armies met again at Cold Harbor a week later.

Today, the 172-acre park has two out-and-back walking trails through pretty woods overlooking the North Anna River. Its rifle pits are considered among the most pristine Civil War earthworks in existence. Much of the western-facing side of Lee’s “hog snout” is intact, as well as the “killing field.”

“You’ve got to get out here and feel it,” says Taylor.

Taylor solicited the help of several groups in the process, including the Blue and Gray Education Society, which created educational signage throughout to give visitors an even deeper appreciation for the hallowed ground they were now able to explore. This was BGES’ flagship project, back in 1998. BGES also created a full-color brochure, 20,000 of which have been disbursed to date.

For Taylor, the restoration of the North Anna Battlefield is part of a larger fight to safeguard our nation’s history in an objective way that takes multiple viewpoints into account. He decries the current push to cleanse America’s past of anything deemed offensive. Taylor believes BGES and other organizations like it are essential to preventing this from happening.

“Right now, we’re running away from our history,” he says. “But there’s room for compromise. We need to add more perspectives that offer additional interpretations, not silence the voices and events from the past that offend us.”