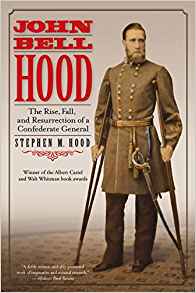

As an award-winning author and the collateral descendant of a much-maligned Civil War figure, Sam Hood knows that retelling our nation’s history accurately often requires digging a little deeper. In fact, part of his impetus for writing John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General was to set the record straight on a man whom many historians have treated unfairly. He followed that with The Lost Papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood, which shed further light on the topic. His next book, Patriots Twice: Former Confederates and the Building of America after the Civil War, will be released in the spring of 2020, by Savas Beatie.

Hood grew up in West Virginia and lived there until 2017. A graduate of Kentucky Military Institute (in 1970) and Marshall University (in 1976), he served in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve from 1971 to 1977. For two decades, he owned and managed an industrial construction company. Hood also spent a good bit of time on soccer pitches, coaching and officiating. His high school teams won four WV state championships, he was named WV high school coach of the year twice, and he’s a member of the WV Soccer Hall of Fame and the WV High School Soccer Coaches Association Hall of Fame. Today, Hood and his wife, Martha, live in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.

BGES Blog: You must be far more knowledgeable about your family history than many of us are. What motivated you to write books about General Hood?

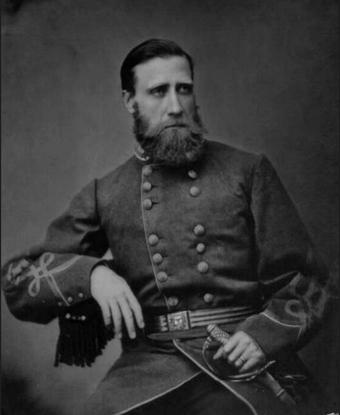

SH: Actually, I am not as closely related to the General as my name implies. I am not a direct descendent, rather collateral, descending from his grandfather Lucas Hood. My interest in Hood piqued in 2000 when I attended a battlefield tour of Spring Hill and Franklin, Tennessee. One of the faculty was the late Wiley Sword, who was a harsh critic of Hood. I wondered how a supposed drug-addicted, lovelorn, homicidal, vengeful, disloyal, mentally unstable, pathologically dishonest, and intellectually ignorant officer could possibly rise to the rank of four-star general. When I returned home I started researching primary source records on what Mr. Sword and other Tennessee Campaign historians wrote and said about Hood.

I was stunned at what I found. Much of Hood’s reputation is based upon, at best, biased interpretations and portrayals that had little resemblance to the primary sources, and at worst, no sources whatsoever—primary or otherwise. I was also astonished at how many primary source records that were supportive, complimentary, or sympathetic to Hood were concealed by authors and historians. Some of these records were so conspicuous and readily available that I became convinced that their concealment had been intentional. All this seemed to me to be unfair, not only to Gen JB Hood’s eternal reputation, but to present-day Civil War students and enthusiasts who innocently were consuming false and fact-filtered information.

BGES Blog: I hear you have a great story about finding and then publishing Hood’s lost papers.

SH: Soon after I had finished the manuscript of John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General, I received a call from a great-grandson of General and Mrs. Hood. He told me that he had received from his mother upon her death in the mid 2000s, several boxes of family letters, documents, photos, and ephemera. He was not an expert on Civil War history and thought that perhaps there might be something in the cache of papers that I might be able to use in my book. I arrived at his home to inspect the papers expecting to find nothing, but was absolutely stunned when I discovered that they were General Hood’s long-lost personal papers, thought to have been discarded or destroyed upon his sudden death in August 1879. His wife had predeceased him two days earlier, and there were ten surviving orphans, all under eleven years old, which doubtless consumed the attention and efforts of the surviving family and friends.

SH: Soon after I had finished the manuscript of John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General, I received a call from a great-grandson of General and Mrs. Hood. He told me that he had received from his mother upon her death in the mid 2000s, several boxes of family letters, documents, photos, and ephemera. He was not an expert on Civil War history and thought that perhaps there might be something in the cache of papers that I might be able to use in my book. I arrived at his home to inspect the papers expecting to find nothing, but was absolutely stunned when I discovered that they were General Hood’s long-lost personal papers, thought to have been discarded or destroyed upon his sudden death in August 1879. His wife had predeceased him two days earlier, and there were ten surviving orphans, all under eleven years old, which doubtless consumed the attention and efforts of the surviving family and friends.

The papers included crucial new evidence on the Army of Tennessee’s failure at Spring Hill, Tennessee, on the night of Nov. 29, 1864, as well as Hood’s alleged secret correspondence with Richmond authorities while serving under Joe Johnston in 1864. Other enlightening papers included Hood’s doctor’s handwritten daily journal of Hood’s Chickamauga wounding, leg amputation, and recovery. It established that Hood was not prescribed opiates for pain, rather only for sleep, and the morphia he was prescribed for sleep was used very judiciously, and that he was weaned off the drug completely by November 1863.

There were also numerous postwar letters between Hood and his wife that revealed his kind, courteous, gentle personality, and his deep religious faith. I quickly transcribed the all the letters, and inserted many new facts into my manuscript before its publication in 2013. I then annotated and published the letters in 2015 in The Lost Papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood.

BGES Blog: You have a new book coming out in 2020 that addresses postwar Confederates who have made a difference in the postwar world. What was the impetus for this book? Do you think it will change any attitudes?

BGES Blog: You have a new book coming out in 2020 that addresses postwar Confederates who have made a difference in the postwar world. What was the impetus for this book? Do you think it will change any attitudes?

SH: Like most—dare I say all—true history lovers, I am distressed at the recent trend of removing and destroying historical monuments. Confederate memorials are the low hanging fruit, and all of our nation’s history is under assault by those who demand that current social values be applied to men and women of the past. I certainly hope the information I present in my new book will change some minds.

I feel that if the men who literally tried to kill each other in the early 1860s could forgive and reconcile, then Americans 150 years later should find it in their hearts to do likewise. Former Confederates were respected and trusted in the decades after the war, rising to positions of prominence in the federal government and society in general. Four former Confederates became U.S. Supreme Court justices (one was chief justice), two became U.S. Navy secretaries, two U.S. attorney generals, and over 70 former Rebels became U.S. diplomats. Eight former Confederate officers became U.S. Army generals during the Spanish-American War. Several former Confederates served as presidents of national professional societies such as the American Medical Association, American Bar Association, and one CSA veteran co-founded the Sierra Club. Many former Confederates founded colleges and universities, several for African Americans and women, and many more became presidents of universities of such unlikely schools as Cal Berkeley. Former Confederates became governors of several states and territories outside of the eleven former Confederate states, and former Rebels were elected mayors of such surprising cities as Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Los Angeles, California. Surely these men should be judged on their full lives, not their allegiances during a four-year war for independence.

BGES Blog: Talk about BGES. What do you like about it?

SH: I have been a BGES supporter and a personal friend of Len’s since 1999. Although I don’t attend as many field trips as before, I still follow BGES activities, and support the organizations projects. With American history ignored and/or under assault in academia and in the media, the work of the BGES is more important now than ever.

You must be logged in to post a comment.