Battles and Leaders of the Civil War [ca 1887] / NPS

Greene’s interest in the Civil War was sparked in his childhood, and grew in intensity after a family trip to Gettysburg. After graduating from Florida State University, he studied as a grad student at LSU under noted historian T. Harry Williams. Greene is a co-founder of the American Battlefield Trust, originally known as the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites, and spent five years as the organization’s first director. He also served as director of Pamplin Historical Park in Virginia. Greene talked with us about the Petersburg Campaign and the BGES tour.

BGES Blog: You refer to the Petersburg as a “Campaign.” Others call it a Battle or even a Siege. Why do you believe Campaign is the most accurate term?

Wil Greene: Really, it’s a matter of semantics. But a battle is a single action, and Petersburg consumed nine and a half months. So I believe calling it a battle is out of the question.

A siege, on the other hand, includes several key components. The army under siege has to be surrounded. That did not happen in Petersburg. Siege tactics are also very specific from engineering and strategic standpoints. Grant authorized siege tactics for a grand total of 36 hours, and they were never actually implemented. Finally, a siege suggests a static arrangement. Though Petersburg if often portrayed that way, it wasn’t really the case.

BGES Blog: The Petersburg Campaign Tour takes place in a month from now, from September 25 to September 28. Tell us a little about it.

Wil Greene: The tour coincides with the first volume of my Petersburg trilogy,ACampaign of Giants. We cover the first three offensives of the Petersburg Campaign. I enjoy this tour because we take people to sites that they’ve likely never seen before. We really get off the beaten path. Even with something like the Crater, we offer a fresh perspective.

BGES Blog: Talk more about the three offensives you mentioned.

Wil Greene: We devote a full day to each offensive. The first took place from June 15to 18, 1864. It starts with Union troops crossing the James River and launching their initial attacks on Petersburg’s eastern defenses. It was incredibly bloody. Union casualties numbered about 13,000, while there were about 4,000 for the Confederate army.

Day two of the tour covers two separate operations—one infantry and the other cavalry—that occurred from June 22 to July 1. The cavalry raid was one of the largest of the entire Civil War. Though the Union troops were defeated, they did manage to disrupt critical Confederate communication lines.

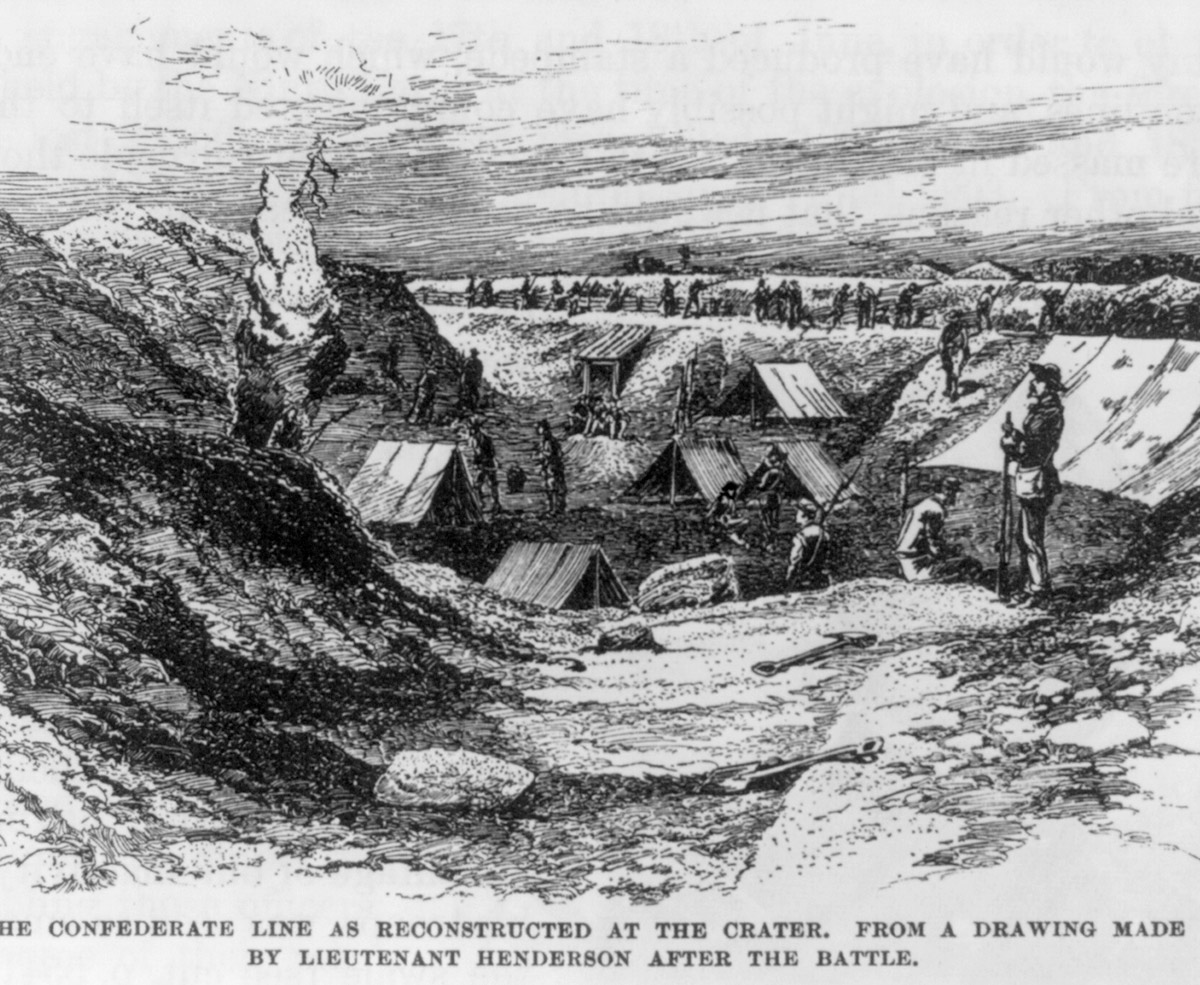

The final day of the tour traces two battles, First Deep Bottom and the Battle of The Crater. Both involved what would become Grant’s pattern: attack north of the James River and extend the Union reach south of Petersburg. The Battle of The Crater would be Grant’s last head-on offensive until April of 1865. He viewed this strategy as too costly in terms of casualties. In fact, Grant called The Battle of The Crater “the saddest affair” he had witnessed in the war.

BGES Blog: The Petersburg Campaign saw the birth of the widespread use of trench warfare. Why? Was this in part due to what Grant’s reaction to The Battle of The Crater?

Wil Greene: To maintain support for the Union effort, Grant understood that he had to show constant progress and prove that the Civil War was winnable. Deadly battles did not help that cause. Trench warfare allowed commanders on both sides to take a more defensive posture. For the Union, that meant the ability to hold lines with fewer troops. For the Confederacy, it meant the ability to simply hold on and survive.

It’s worth noting that quite a bit of these trenches remain, on public and private grounds alike. We’ll take a good look at them during the tour.

BGES Blog: As you noted, the Petersburg Campaign was a long series of attacks and counterattacks that lasted 292 days. Did the change of seasons affect military strategy? How was morale on both sides?

Wil Greene: The change of seasons had a significant impact. During the winter in the Petersburg area—November through March—the temperature during the day was usually above freezing, but it fell below that at night. This created very difficult conditions for wheeled vehicles. Troops were often immobilized, and the Confederate army was relegated to a strictly defensive position.

Grant was well aware that he had to make continued inroads to sustain a winning strategy. In early February 1865, when the weather unexpectedly warmed up, the Union took the opportunity to launch an offensive resulting in the Battle of Hatcher’s Run. It was part of Grant’s strategy to cut off Confederate supply lines and take control of all the railroads.

Union morale was usually high despite very poor living conditions. The troops were definitely bolstered by the re-election of President Lincoln. The opposite was true for Confederate troops. They saw unprecedented levels of desertion during this time.

BGES Blog: Virginia had a large black population, more than 500,000 in all. What role did African-Americans play in the Petersburg Campaign?

Wil Greene: Many people forget that Petersburg was the second largest city in Virginia and the seventh largest in the Confederacy during this time. It also had the largest percentage blacks as a proportion of the free population. Interestingly, hundreds of these men volunteered for the Confederate army. They were perhaps trying to get on the “right” side if the Confederacy won. They were refused as soldiers, of course, but worked tirelessly to build trenches.

The Union employed two divisions of United States Colored Troops, some former slaves from Virginia and other Southern states. In fact, Petersburg was the first time in the war’s Eastern Theater that African-Americans made a significant contribution in battle.

BGES Blog: Place the Petersburg Campaign in proper context. How is it viewed historically in terms of its impact on the Civil War?

Wil Greene: We all know that eternal and unanswerable question of the Civil War: What was the turning point? I would argue for the Petersburg Campaign. Up until this point, the Confederate resistance seemed unconquerable to many and led to pessimism from the Union. Coupled with the re-election of Lincoln, Petersburg proved that the Union could and would win.

You must be logged in to post a comment.