Parker Hills is an expert when it comes to military strategy. The Mississippi native and graduate of the U.S. Army War College served more than 30 years in the U.S. Army, retiring as brigadier general in 2001. He owns Battle Focus, a leadership training company that trains soldiers, airmen, and Marines, as well as corporate leaders and even tourists.

He also happens to be the nation’s foremost historian on the Vicksburg Campaign. Among his accomplishments, he’s written several books related to the topic, including A Study in Warfighting: Nathan Bedford Forrest and the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads and co-author with Edwin C. Bearss of Receding Tide: Vicksburg and Gettysburg.

So when it comes to delving into the relatively obscure stories related to Vicksburg, you would be hard-pressed to find a better leader to take you there.

Over the past three-and-a-half-years, Brig. Gen. Hills has already provided BGES tour participants with fascinating insights into such events as Forrest’s and Van Dorn’s late 1862 cavalry raids in West Tennessee and North Mississippi; and Grant and Porter’s perambulations of the swamps of the Bayou Expeditions in Mississippi and Louisiana during the winter of 1863.

And now, in the final installment of the four-year Vicksburg series—”Unvexed to the Sea” The Mississippi River is Reopened,” taking place this February 2022—Brig. Gen. Hills explores rarely told tales related to the southern component of the campaign, including the battle of Plains Store and progress to operations against Port Hudson. This tour promises to take participants where others cannot.

We caught up with Brig. Gen. Hills to find out what he has in store for this long-awaited signature tour, as well as to better understand his deep connection to Vicksburg.

BGES Blog: “Unvexed to the Sea: The Mississippi River is Reopened” is the final installment in the four-year Vicksburg series. What should attendees expect? What are some tour highlights?

PH: Our last program was Vicksburg 7, conducted in March 2020, just before the pandemic hit. Thus, this final program of the Vicksburg Campaign series has been delayed for almost two years. In our penultimate program, we wrapped up Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign by covering the various siege operations, then we followed all of the routes to the unmarked sites of the Second Front, where Gen. Joseph E. Johnston and Maj Gen. William T. Sherman sparred, but never totally engaged, until Johnston withdrew back into Jackson, Mississippi.

In Vicksburg 8 this coming February, we will turn our attention to the operations regarding the final Confederate bastion on the Mississippi River, Port Hudson, Louisiana, which is just over 16 miles north of Baton Rouge. The significance of the guns of Vicksburg and of Port Hudson was that the South could still somewhat control 120 miles of the Mississippi River (as the crow flies) between the two fortified positions. Even though some Union vessels of war had run the batteries of Vicksburg and Port Hudson and were operating in this disputed area, the river was still closed to commerce. President Abraham Lincoln desperately needed to restore that commerce, and opening the Mississippi River was his strategic goal. Also, the Red River, which flows across central Louisiana and empties into the Mississippi 30 miles northwest of Port Hudson, allowed the South to bring vital supplies across the Mississippi River from the West.

But it is not simply a Port Hudson program. While the Union Army of the Tennessee was maneuvering in Mississippi, the 19th Corps of the Army of the Gulf was maneuvering in Louisiana, with both army commanders hoping to win the prize offered by the Secretary of War on March 1, 1863—that being promotion to Regular Army major general to the first general who won a significant victory, regardless of date of rank. So, while the Army of the Tennessee was maneuvering far east of Vicksburg in the Mississippi interior, the Army of the Gulf was maneuvering far west of Port Hudson and deep into Louisiana. We have covered the maneuvers in Mississippi in detail in previous programs, and now we will cover the maneuvers in Louisiana in detail, to include the Bayou Teche Campaign, much of which is unmarked and rarely discussed.

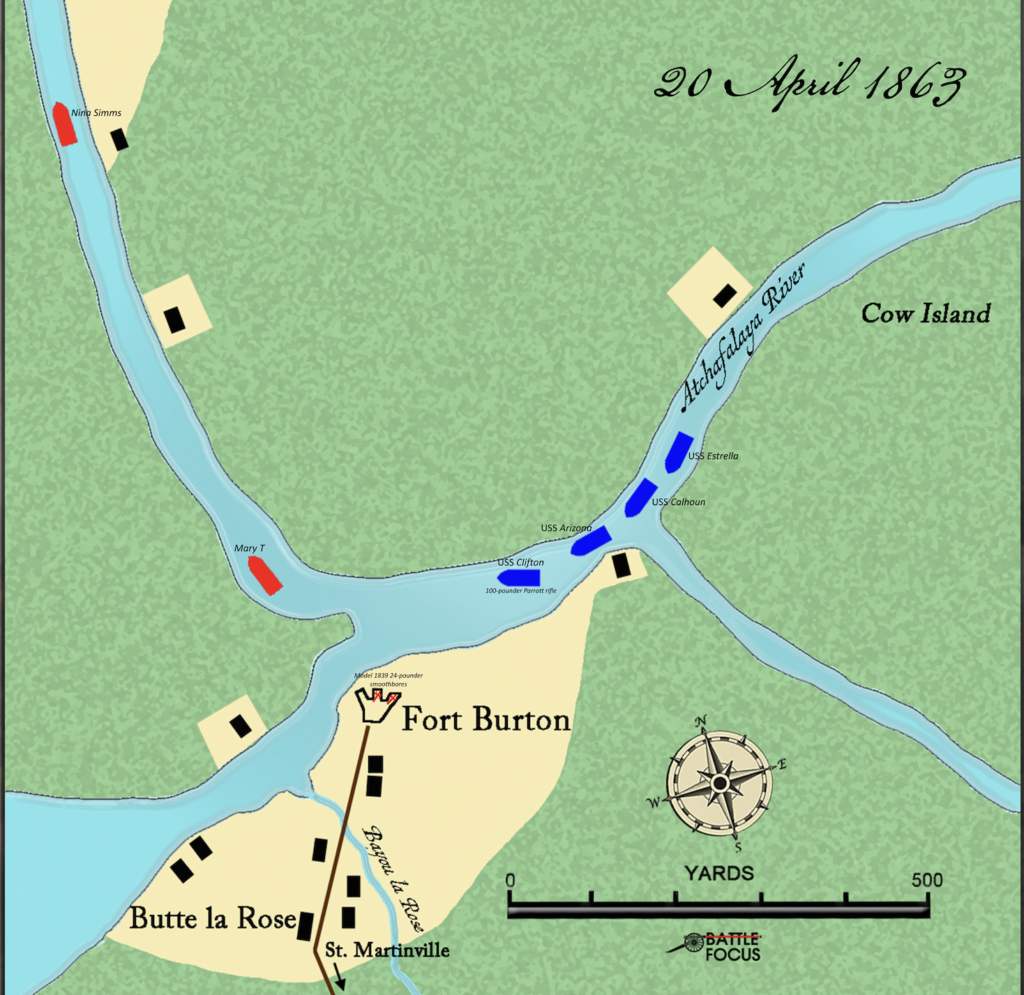

This final tour of the Vicksburg series has been totally re-worked to do what Blue and Gray Education Society does best: Go where others do not. An extensive new series of field briefing maps has been developed to aid in understanding the actions, and we are fortunate that much of the area that we will travel is still interpretable. Although the sites are rarely marked, we will visit them to fully comprehend this rarely discussed part of the War. I attach a sample of one of these maps (see above), the Confederate attack on Fort Burton at Butte la Rose, Louisiana, a site never before visited by Blue and Gray.

BGES Blog: Who are the major players in this part of the Vicksburg Campaign? What interesting historical figures might attendees be meeting?

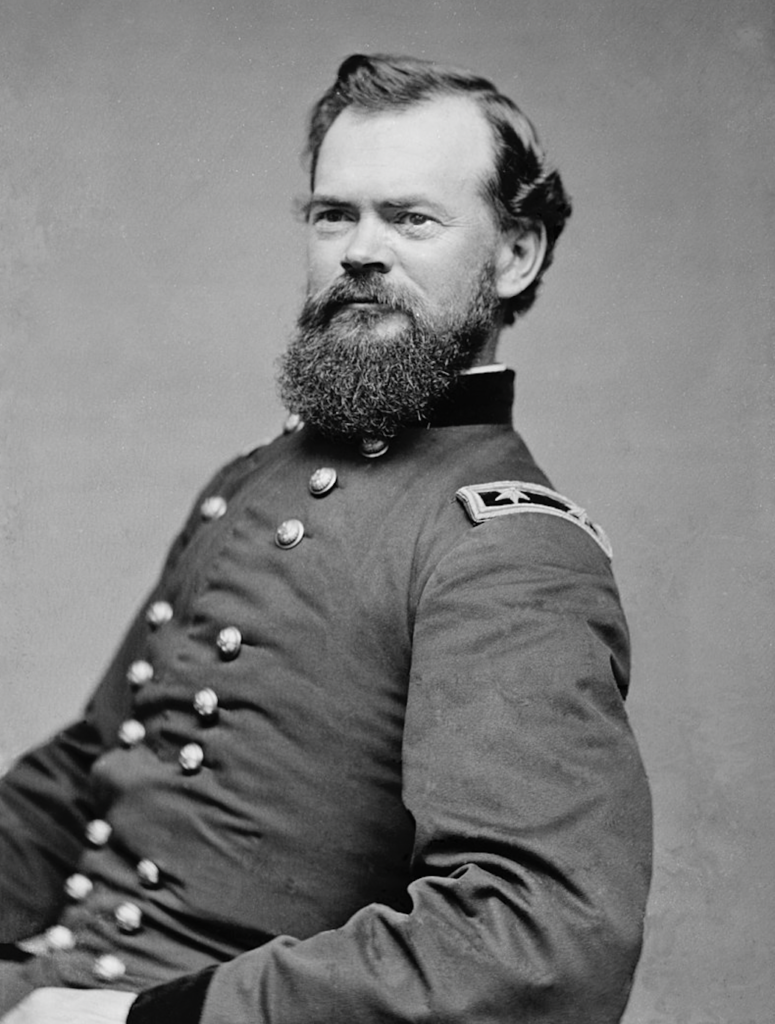

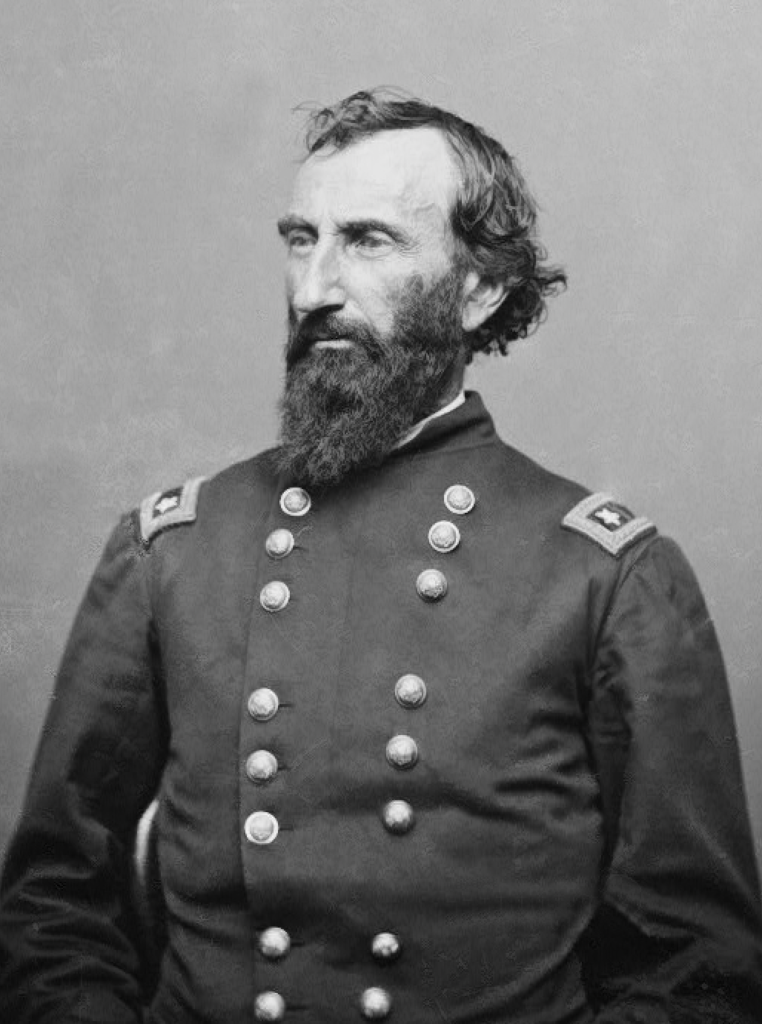

PH: Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks commanded the Army of the Gulf for the North, while Maj Gen. Franklin Gardner commanded the Third District, Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana, for the South. For ease of memory, let’s just say Gardner commanded Port Hudson. Interestingly, Gardner’s photograph is often mislabeled as that of Brig. Gen. Richard Garnett, who was killed at Gettysburg. And we cannot forget the Union Navy, which was the West Gulf Blockading Squadron commanded by Adm. David Glasgow Farragut, a name that clangs like a cutlass. Then, as we follow Banks on his Bayou Teche Expedition, we will meet the feisty Confederate Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor commanding the District of West Louisiana.

Some interesting characters we will discuss on the Confederate side are Brig. Gen. Alfred Mouton of Louisiana and Confederate Col. Tom Green of Texas, both of whom were killed during the Red River Campaign of 1864. In fact, we will visit Mouton’s grave in Lafayette, Louisiana. There is Confederate artillery battery commander, Capt. Oliver P. Semmes, son of the famed Capt. Raphael Semmes of CSS Alabama fame, who will also serve as captain of the captured Union gunboat, Diana, on Bayou Teche. We will discuss the actions of Lt. John West and his section of 10-pounder Parrott rifles as they fight a delaying action with Tom Green at Centerville, Louisiana. And we will walk in the steps of the obscure Catholic priest, Father Francois Mittlebronn, along False River, Louisiana.

On the Union side, we will discuss one of Banks’ favorites, Brig. Gen. William Dwight. Some may remember Dwight’s brief appearance at the Battle of Big Black Bridge on May 17, 1863, when he delivered General-in-Chief Halleck’s message to Grant and was rebuffed by that cigar-chomping commander. Of course, we will talk about Brig. Gen. Benjamin Grierson, who rode into Baton Rouge to conclude his famous Vicksburg Campaign raid on May 2, 1863, only to find himself drafted into Banks’ ranks. We will learn more about “the other Sherman,” the beardless but elaborately coiffed Thomas Sherman. We will also visit the grave of Navy Lt. Comm. John E. Hart in St. Francisville, Louisiana, and we will discuss his relationship with Father Mittlebronn.

BGES Blog: What is your personal connection to Vicksburg? What is your personal interest in telling these stories? Can you give us a quick vignette that might give us a flavor of the tour?

PH: I grew up in the heart of the Vicksburg Campaign, and I now reside there. In fact, one of the major old sunken roadbeds used by the troops during the Vicksburg Campaign runs just south of the lake where my wife, Carol, and I reside in Clinton, Mississippi. Ulysses Grant spent the night of May 15-16, 1863, at Greenwood Plantation, and the old plantation cemetery is on the modern Natchez Trace one-half mile north of our home. On that night in May, which was the night before the crucial Battle of Champion Hill, Grant accomplished what I believe to be the supreme military intelligence coup of the Civil War.

And I was born and bred in Jackson, Mississippi, which was burned to the ground four times during the Civil War. Of course, Jackson is only 45 miles east of Vicksburg, and treks to that military park were a wonderful tradition as I grew up. The Civil War Centennial of the 1960s, which unlike the Sesquicentennial of this century, was a huge commemorative event, and it took place while I was attending junior high school. In fact, I played hooky so that I could go downtown to see the huge parade of military units, followed by a massive display of artillery firing. I remember those booming cannon as though it were yesterday, but I cannot recall any of the details of the punishment I received for ditching school that day. So, that is my connection.

My purpose in telling these stories is to honor the soldiers who participated in these events. And there are wonderful leadership lessons to be gleaned from them. One of my favorite lessons is when General Grant initiated his final offensive on Vicksburg, and it took place only a few days after General Banks began his Bayou Teche Campaign in late March 1863, which was no coincidence. Remember the promotion offer of March 1? By late March, both Grant and Banks had begun their maneuvers to capture Vicksburg and Port Hudson, respectively. But when Grant announced his plan to march south through Louisiana, then cross the Mississippi below Vicksburg, two of his three maneuver corps commanders said they thought the plan too risky. William T. Sherman, Grant’s best friend in the army, advised Grant that he would be “putting [himself] in a position voluntarily which an enemy would be glad to maneuver a year–or a long time–to get [him] in.”

James B. McPherson, Grant’s protégé, who had been promoted by Grant from captain to major general in fourteen and one-half months, agreed with Sherman. But John A. McClernand, a political general, understood President Lincoln’s need to get the Mississippi River open to commerce as quickly as possible, so he agreed with Grant. Now, there was no love lost between McClernand and Grant, and McClernand was an outsider in that, unlike Grant, Sherman, and McPherson, he was neither a West Pointer nor an Ohioan. Yet, McClernand believed in the mission and Grant made a decision that was unpopular with almost everyone: He gave McClernand the honor of leading the march south as the tip of the spear. The leadership lesson is, never delegate to someone who does not share your vision.

For a quick vignette, during this tour, we will travel to an expanse of open fields near Bayou Clause on the west bank of the Mississippi River, a scant seven miles below Port Hudson. Here, on the night of March 18, 1863, the Confederates basically played a prank on Banks. While the guns of Port Hudson blasted away at Farragut’s fleet to create a diversion, a number of adventurous soldiers in gray cut a gap in the Mississippi River levee just downstream from where Banks’ headquarters boat and three other Union transports were anchored at the west bank. During the night, the river flooded into the open fields and sucked all four boats toward the crevasse. The next morning a surprised and humiliated Banks and his commanders awoke to find the transport Morning Light stranded 200 yards from the Mississippi in the middle of a cane field, while the other boats had been pulled into the crevasse and grounded where the levee once stood.

Why this tour? What will you offer that the others won’t?

As I have mentioned, we will go where other tours never venture, and we will see the untold sites that are part of the story of opening the Mississippi River. So, this is not a tour of monuments and cannon. It is a tour of the Louisiana landscape, although we will eventually some cannon and markers at Port Hudson. I worked my way through college in the oil fields in this part of Louisiana, and I later bought some property not far from False River. So I know that the area is beautiful, that the people are happy and friendly, and that the food is wonderful. Speaking of food, we will plan to lunch one day on Avery Island, where Tabasco sauce is made.

What on-the-ground elements are you excited to share with tour participants?

I have been studying the Civil War maps as well as the oldest topographical maps that I can find, usually around 1908 or so. By doing so I have located sites that are both unmarked and unappreciated. Of course, I am anxious to take the group to known sites, such as LCDR Hart’s grave in the beautiful cemetery in St. Francisville. But I am equally looking forward to going to obscure sites, to include where the 325 Texans of the “Mosquito Fleet” paddled their way across Grand Lake and Flat Lake to land their 53 vessels, which were basically pirogues, or canoes, and capture the Union garrison of Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) on June 23, 1863. We will visit the site of the Battle of Lafourche Crossing, fought on June 20-21, 1863, where the Confederates, fresh from their capture of the garrison at Thibodaux, Louisiana, charged into death and defeat in front of the Union guns south of the city along the railroad. We will go to Port Barre, which was a major Union supply depot at the junction of Bayou Courtableau and Bayou Teche, and we will travel to Morganza, Louisiana, where Banks embarked with a division to begin the siege of Port Hudson. While at Morganza, we go off-subject to visit the site of Melancon’s Café, where a pivotal scene was filmed for the 1968 cult classic, Easy Rider with Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Jack Nicholson. I think there will something for just about everyone on this tour.

Is it necessary to have attended the previous tours to get the most out of this one?

It’s certainly not necessary to have been on the previous seven tours of this series because the stage will be set on the first and second nights through PowerPoint programs at the hotel. I have worked for months on these programs, and they are designed to lay the foundation, and then explain what will be seen on the tour. Of course, the better read one is, the better prepared they will be for a meaningful experience. And if there is one thing that I have learned over the years, it is that when I read about a campaign or battle, I form a mind’s-eye picture of the ground. Virtually every time I visit those sites for the first time, I find that my mind’s eye was totally inaccurate. The ground never looks the way that I imagined it.

What do you hope your tour adds to the overarching discussion about what the Civil War means today?

We have all basically been taught that the most hallowed ground is the bloodiest ground, and the most common question I am asked on a tour is, “What were the casualties here?” So we have been more or less programmed to believe that the more bloody the ground, the more important it is. I have never believed this, and I hope that the people attending this tour will see how much can be accomplished without the unnecessary spilling of blood. I am more interested in where the gray matter was burned, not the gunpowder. Still, we will visit hallowed ground, and once we get to Port Hudson and see the fields, swamps, and ravines where the futile and very costly assaults were made, I hope that the point of accomplishing the mission with as little human loss as possible will resonate.

Any last words?

Y’all come!

“Unvexed to the Sea: The Mississippi is Reopened” takes place Feb. 15–20, 2022, starting from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Get more info and register here.