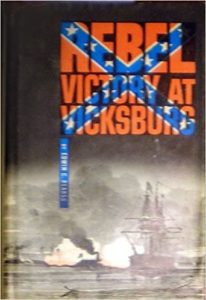

Rebel Victory at Vicksburg

By Edwin Bearss (Pioneer Press, 1963)

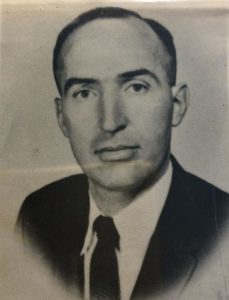

The legend outlives the man and our memories of Ed Bearss long overshadowed our objectivity, and so picking up a book written before Ed became a legend is both daunting and filled with land mines. What if he was all bluster, a showman who was in the right place at the right time and who had the bully pulpit by being in D.C. for 40 years? Don’t worry, it wasn’t all bluster, and indeed it is a refreshing and objective look at how this World War II hero recovered from his war wounds and started anew. We, of course, know that this Marine was wounded in the South Pacific and was in the hospital for nearly three years recovering from his war wounds. I have seen his torso and the horrific scarring caused by Japanese machine gunners—his life was very much at peril. From this event arose the man we learned to follow and love.

We must remember that Ed was an educated man. Using veteran’s educational benefits, he graduated from Georgetown University and then took his graduate studies to Indiana University, where he achieved a Master of Arts degree and was working on his doctoral degree when life intervened and he needed to make a living. After a short stint in a government job, he transferred to the National Park Service and was soon assigned to Vicksburg National Military Park some 60-plus years ago. Armed with a photographic memory, an unquenchable thirst for knowledge, and an ability to draw stories out of locals who had lived and worked the lands around Vicksburg for generations, he earned the respect of the community, even marrying a local historian with whom he shared more than 50 years of marriage and fathered three children.

The sixties in America were the Centennial of the American Civil War. The country was simmering with discontent that would erupt in civil rights violence in the later part of the decade. Civil rights legislation prompted violence and resentment in the Deep South, which was dealing with the ramifications of Brown vs. the Board of Education in Little Rock, Arkansas. Black college students were being escorted to classes at white flagship universities in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and elsewhere. A national Civil War Centennial Commission was chartered, chaired by U.S. Grant’s great-great-grandson.

All this relates because this book is provocative and perhaps a statement “Rebel Victory at Vicksburg.” The title is spelled out on the dust jacket in a red, white, and blue contrast that displays the Confederate Beauregard Battle Flag on the front cover. A screened image of a naval engagement fills out the remainder of the cover. When you open the front cover, you learn the book has been published by the Vicksburg Centennial Commemoration Commission. It was officially published on July 4, 1963—the one-hundredth anniversary of the surrender of Vicksburg. The city never accepted that outcome in the intervening years, and the city had not celebrated the Federal holiday for more than 100 years. That the book is the official publication of the Commemoration Committee, Rebel Victory reeks with irony and perhaps no small amount of symbolism. Do not let that fool you.

Ed Bearss was a historian, and it shows. Do not be taken off the trail by the symbolism. Indeed, over Ed’s career, the incongruence of this centennial publication will be balanced by his subsequent works—the Vicksburg Campaign trilogy written and published for Morningside Books in the early 1980s, and his integrated analysis of Vicksburg in the national strategy revealed in his 2010 publication Receding Tide, with J. Parker Hills and published by National Geographic. Bearss wrote this early work in the first decade of his Park Service career, when he was approaching 40 years of age. He had already begun to establish his niche with an earlier book, Decision in Mississippi, published the year before. He had also written more than 10 scholarly and peer-reviewed articles for credible historical societies and publications in Iowa, Kentucky, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee, as well as professional publications such as The Military Engineer and Military Affairs. These are not publications with widespread distribution in the popular history market. By the time he writes this book, he has helped establish the Civil War Roundtable of Mississippi and he has done intensive studies of Stones River, Five Forks, Pea Ridge, and Wilson’s Creek—the later two will become National Military Parks, and Five Forks will receive its own NPS Visitor Center. He also has already located the resting place of the Federal gunboat U.S.S. Cairo, sunk in the Yazoo River by a mine in December 1862.

So why do I like Rebel Victory? Historically it details a story that generally gets short service in Civil War historiography. In April 1862, New Orleans and then Baton Rouge fall to the Union Navy with supporting infantry. Lincoln would like the Mississippi, which had been closed to commerce to western loyal states for more than a year, to be reopened. Farragut is required to press upriver at a time when the river will begin to run low after the winter snows have melted. His ocean-going vessels are not designed for the brown water of the rivers, especially when the depth varies so much and the river is a large drainage sewer filled with snags and large logs that are being carried to the Gulf of Mexico. Farragut complies and takes Natchez without resistance, but is defied by the civilian leadership of Vicksburg. Farragut prefers to drop downriver, only to find the Federal leadership in Washington insists he press the objective. This book is that story, and of course we know the Federals failed.

There are several items that bear consideration.

First, Bearss is clearheaded and thorough. He easily integrates the official records of both the armies and the navies to extract the official story. Bearss then taps the resources of the state’s archives and history, drawing out the first-person accounts of local militia and units assigned to the defense of the region. Where he is lacking in expertise he finds the experts, not people with opinions but rather experts such as William Geoghegan at the Smithsonian Institute for answers about ship construction and the unique language of naval construction and communications. He asks retired military men to look into the resources of the National Archives to bring to bear items that don’t appear “online” or are sent by email. He has bountiful resources at Vicksburg NMP, but he also plumbs his colleagues at other sites. So more than 60 years ago, when research trips involved long trips by train or motor car on two- and four-lane roads for hundreds of miles, he not only gathers the sources but documents each, so any person like me—58 years later—can find his source quickly and unambiguously. As a historian, any historian, he is teaching us the right way.

The legend became an entertaining showman in which people marveled at his mastery of the most minute detail—such as the company in the regiment that lost three men at some remote element of the event described. In this, you see a man who is not that legend, but who communicates without misstep. The prose is not dramatic. Indeed, those who can hear Bearss’ thundering voice in the field embedded in their brains—it does not resonate within these pages, but you learn and you understand.

You do not see this book very often, and I am certain that even in Mississippi today you would not see the dust jacket that is on the first edition that I have. It is 285 pages with endnotes for each of the 10 chapters. It is not footnoted to a distracting degree, but there is no doubt that his narrative is based on “the record.” This is a legacy book that, looked at through various lens, will inform you about the antecedents of the more famous Vicksburg Campaign, but more importantly will introduce you to the antecedents of Ed Bearss before he was a legend.

You must be logged in to post a comment.