As any good writer knows, you’re never really sure what you’re getting into when starting a new project … until you’re ready to submit it. Even then, there are always more surprises awaiting you, and the final product often looks different from how you originally envisioned it.

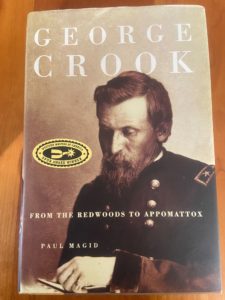

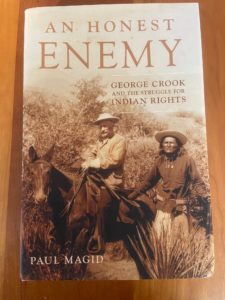

Paul Magid learned this lesson first-hand when he embarked on a biography of Maj. Gen. George Crook in 2002. A first-time author, Magid eagerly dove into his research of the famed military officer, and soon realized that one book would not do. Fast-forward to 2020—and thousands of pages later—as Magid completed his epic three-volume tome to Crook. The first in the series, George Crook: From the Redwoods to Appomattox, was released in 2012. Magid followed that a few years later with The Gray Fox: George Crook and the Indian Wars. The final volume, An Honest Enemy, George Crook and the Struggle for Indian Rights, came out this past year.

The trio of books comprises the most detailed and compelling works ever written on Crook. The BGES Blog sat down with Magid to discuss the twists of fate that led him from a career as a marketing executive to an acclaimed historian and the kindred spirit he found in Crook.

BGES Blog: Let’s start with a question you’re asked all the time. Why did you turn your attention to George Crook? What about him captured your imagination?

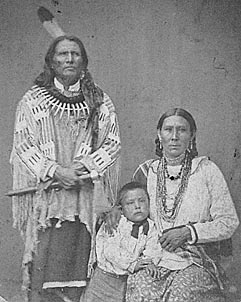

PM: My fascination with Crook derived from my interest in Native America, dating back to my childhood. Though born and raised in Westchester County, New York, like many of my contemporaries, I grew up immersed in a pop culture that at the time was more often oriented around American history than superheroes. In the 1940s and early ‘50s, it was the Second World War and the Old West that held our attention. For 25 cents, we would spend an entire Saturday afternoon at the movies watching John Wayne or Burt Lancaster fight Indians, outlaws, Germans, or Japanese. The rest of the week, when not in school, we reenacted our favorite heroes’ adventures in the woods around our house and read comic books about Red Ryder and the Lone Ranger. We ate cereal (shredded wheat) that featured Straight Arrow “Injunuity Cards,” a great way to learn how to build a teepee or identify those mysterious cougar tracks in Mom’s flowerbed, or chewed bubblegum that featured cards portraying not only baseball players but also Indian chiefs like Cochise and Sitting Bull. On the radio, it was the Lone Ranger and his sidekick, Tonto, and when TV first appeared on the scene, old cowboy movies from the ’30s were a staple.

Since pop culture rarely provided an accurate picture of history, I think the most important influence in shaping my interest in Native America and America’s westward expansion was the grade school I attended. A small country school, each year’s curriculum was built around a central theme. The theme for the fourth grade was the American Indians—their culture, lifeways, and history, divided by regions—beginning with the Eastern Indians and then moving on to the Southwestern, Great Plains, and the Pacific Northwestern tribes. To supplement classroom lessons, we visited the New York Museum of Natural History and viewed its collection and dioramas of Indian life, built a Navajo Hogan in the woods near the school, and, most importantly, read books, fiction, and nonfiction, that described in great detail Indian life.

BGES Blog: But you didn’t stick with history as your academic career advanced. Why? Did something change?

PM: In college, I majored in history and, because I loved it, did well. But when one of my professors urged me to continue on to graduate school in the discipline, I backed off. I thought it might be impractical to pursue a career in academia and did not see myself as a teacher. Instead, I went to law school “to learn a more practical trade.” While still at school, I attended my sister’s college graduation. Sergeant Shriver was the guest speaker and his topic was the Peace Corps. By the time he finished his speech, I had decided to volunteer. The year was 1966 and Vietnam was in full swing. I was drafted, so my entry into the Peace Corps was delayed by two years of military service, most of it spent at Fort Ord in California, which allowed me to explore the West, from Alaska to Arizona.

After my discharge, I entered the Peace Corps. I spent two years as a volunteer in Africa—I was a secondary school teacher in rural Malawi—and then backpacked for a year throughout Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. I returned to the States to find employment with the Peace Corps in Washington in their General Counsel’s office. From there, I went on to become General Counsel for the African Development Foundation, a small U.S. government agency, continuing my career in grassroots international development.

BGES Blog: You retired in 1999 after 30 years of international work, and then revisited your love of history. What was the impetus?

BGES Blog: You retired in 1999 after 30 years of international work, and then revisited your love of history. What was the impetus?

PM: I was ready to retire, but not to sit on the couch. I had developed some facility for writing over the years and, when I retired, I honed these skills by enrolling in a Master’s degree writing program. My ambition was to return to my childhood interest and my roots in college history. I had decided to resume my studies of the Native American tribes and, as I am also interested in military history, use what I learned to write a book about the Indian Wars on the Western Frontier. To tie the work together, I looked for a historical figure, perhaps a scout or career soldier, whose career spanned the years of westward expansion, through whose eyes and experiences I could tell this story.

That is when I stumbled on General Crook. I watched the movie Geronimo, not particularly historically accurate, but otherwise an interesting film with an intriguing portrait of Crook (who was played by Gene Hackman). The film portrayed him as a professional Indian fighter of considerable note, but someone deeply committed to the welfare of his Apache scouts and by extension, the Apache tribes whom he had so vigorously suppressed in his role as commanding general of the Department of Arizona. I found this combination of warrior and humanitarian fascinating, and a sign of a complex and perhaps conflicted personality. I read his autobiography, a brief and somewhat confused recitation of his life from his graduation from West Point to the Battle of the Rosebud in 1876. A quick Internet search revealed that no full-length biography had been written and that other than his autobiography, only a memoir by his aide, John Bourke. Since he graduated from the Academy in 1848 and, except for the Civil War, served his entire career on the Western Frontier, up to his death in 1890, nine months before Wounded Knee, he seemed to perfectly fit my needs.

BGES Blog: So that set the stage for George Crook: From the Redwoods to Appomattox, your first book on him?

PM: Yes, but when I began work on Crook’s biography in 2002, I had no idea that it would wind up as three books. I began it as a single work while in the Writers graduate program. Several years later, I had 1,400 pages written and was still only about three-quarters of the way to the end. At that time, I had no agent and no solid plans for publishing the work, though I had a dim notion that it would be wonderful if I could get the University of Oklahoma Press, the premier publisher of works on Western history, to publish it.

Then serendipity intervened. Around 2007, I attended a symposium on Western History at Fort Robinson, the historic Army post built on the Red Cloud Reservation in Nebraska. During a break, I was telling some of the attendees, most of whom were professional historians, about my project and was overheard by a man who later approached me and asked me more about it. After we had talked a while, he said that when I was ready, I should send him the manuscript and he would be happy to look it over. He then identified himself as Robert Clark, at the time the publisher of the Arthur C. Clark imprint of University of Oklahoma Press. This serendipitous meeting allowed me to interact with a well-known, established press without the benefit of an agent, and I have never gotten one. I don’t necessarily recommend this process to other would-be authors. As will become obvious, I was extremely lucky to stumble into this relationship.

Then serendipity intervened. Around 2007, I attended a symposium on Western History at Fort Robinson, the historic Army post built on the Red Cloud Reservation in Nebraska. During a break, I was telling some of the attendees, most of whom were professional historians, about my project and was overheard by a man who later approached me and asked me more about it. After we had talked a while, he said that when I was ready, I should send him the manuscript and he would be happy to look it over. He then identified himself as Robert Clark, at the time the publisher of the Arthur C. Clark imprint of University of Oklahoma Press. This serendipitous meeting allowed me to interact with a well-known, established press without the benefit of an agent, and I have never gotten one. I don’t necessarily recommend this process to other would-be authors. As will become obvious, I was extremely lucky to stumble into this relationship.

A year later, with some trepidation, I sent Clark the 1,400 pages, and he soon responded that he liked what I had written. If I could cut it down to a book of around 300 to 400 pages, the Press might be interested in publishing it. I was both elated and crushed. Cutting over three-quarters of my manuscript seemed like a daunting task. After several sleepless nights, I came up with a counter-proposal. (Had I known anything about publishing, I would never have had the audacity to make it.) I proposed that I provide a biography of Crook that covered his early career through the end of the Civil War. With the war’s sesquicentennial soon coming up, interest in the Civil War was then peaking. If accepted, I said that would cover the rest of Crook’s life in a second volume. The Press could accept or reject depending on the success of the first and the quality of the second. Clark, being an exceptionally decent and kind individual, agreed in principle.

That was in 2011. I then underwent an arduous multistep review process. Clark reviewed the manuscript, and then passed it on to two Western historians to determine its historical accuracy. They submitted a list of suggested changes, which I made, and then the work was resubmitted to a panel of staff members from the Press to determine whether it would be economically desirable to publish it.

Somehow, as a first-time, never-published author, I made it over these hurdles and the book came out in 2012. It subsequently received a Spur Award from the Western Writers of America as the best biography of a Westerner for that year. The award was presented by Wes Studi, the actor who portrayed Geronimo in the movie that had started it all for me. It was the highpoint of my life as an author.

BGES Blog: George Crook: From the Redwoods to Appomattox focuses mostly on Crook’s role in the Civil War, but you also chronicle how he prepared for that experience with nearly a decade of military service in California. What did Crook learn during this period that he took with him into the Civil War?

PM: Though over half the first book deals with the Civil War, I would say that taking Crook’s career in its entirety, the war itself was an interruption in a lifetime spent dealing with Indians on the frontier. Most of what he learned on the West Coast, which gave him an insight into the Indian mind, prepared him for his postwar duty in Arizona, Montana, Idaho, and Nevada. But he did bring a good deal of knowledge and experience about guerilla warfare to his Civil War service, learned during his initial service on the coast because the style of fighting used by the Indians was very similar to partisan warfare. Most officers in the regular army did not have this type of experience at the time and very little was known or taught at West Point about guerrilla warfare.

Crook’s reputation as an Indian fighter led to an assignment in western Virginia fighting Confederate bushwhackers and partisans. Using Indian fighting tactics, he was very effective in reducing the partisan threat in his area of combat. He also later employed lessons learned in Indian warfare in more conventional campaigning, including how to maneuver in dense forest and deceptive tactics that concealed his presence from his enemy and disguised his route or his intentions. These tactics were particularly useful when he commanded small highly mobile units. Later on, of course, they became somewhat less useful as he rose in the ranks to command larger units engaged primarily in conventional warfare and larger battles fought more conventionally.

After the battle of Fisher’s Hill, won largely due to Crook’s planning and leadership, Sheridan took all the credit for the victory. Together with a lifelong grudge against his former friend, Crook took from this incident one bitter lesson that he carried with him throughout his career. In the military, he believed, it was not what you achieved, but how you touted it and whom you knew that affected your career. Whether his belief was well-grounded, it certainly affected his state of mind and various stages of his career.

BGES Blog: You also detail Crook’s capture by partisans during the final months of the Civil War. How did the experience shape him?

BGES Blog: You also detail Crook’s capture by partisans during the final months of the Civil War. How did the experience shape him?

PM: The plan to capture Crook was a daring one and almost netted the raiders three future presidents in Hayes, Garfield, and McKinley, who were present or near Cumberland, where the raid took place. Crook recognized and appreciated the élan and courage of the raiders in carrying it out, and though he realized it might harm his career, he seemed to have enjoyed the adventure and established a rapport with the partisans. They, in turn, came to respect him. In fact, one became his future brother-in-law after the general married his sister, and several attended his funeral years later. It turned out that the kidnapping did not affect his career, though it seems clear that, thereafter, he held no animus toward his captors or confederates in general.

BGES Blog: The next book in the series, The Gray Fox: George Crook and the Indian Wars, examines Crook’s career after the Civil War, as he became the nation’s leading expert in Native American warfare. But once again, there were some bumps in the road in the writing of it, correct?

PM: Of course, I discovered that there was no way that I could complete Crook’s biography in one additional volume, at least not with the level of detail I considered warranted. A new editor, Charles Rankin, had replaced Robert Clark by the time I was ready to submit the second volume, He proved as supportive and understanding as Clark. I approached him nervously with the same type of proposal I made for the first book. He agreed to take a look at the work and ultimately, after going through the same procedure as the first book, it too was published and was a finalist for the same award from Western Writers. This time, first place went to Pulitzer-Prize winner TJ Stiles for his Custer biography.

BGES Blog: You titled this book The Gray Fox. The Apache nicknamed Crook “Chief Wolf.” Why the association with wolves and foxes?

PM: It has been well established that the Apache word nantan means “chief” or “boss.” But there has been some controversy about whether the term lupan means “wolf” or “fox” in the Apache language. Since the tribe did not have a written language at the time, the term they used to describe Crook could only have been approximated by its listeners, so it may have been corrupted beyond recognition. That may explain why on visits to the Apache reservation, when I asked several members of the tribe the meaning of the term, the Apaches I talked to did not know what it referred to, though some thought it might refer to the coyote, often revered by Indians for its cleverness.

Some contemporary writings by officers who served with Crook, as well as former scouts, journalists who befriended and wrote about him, and subsequent historians, called him Chief Gray Fox. Others called him Chief Gray Wolf. I went with fox because most of the officers and journalists closest to Crook referred to him that way. I was also influenced by a reference in a work of Apache anthropology. The author wrote that the appearance of a gray fox was regarded by the Apaches as a harbinger of impending death.

Crook was given this name following a relentless campaign against the Apaches in Arizona during which his troops hunted down and subjugated the Western Apaches. It seemed logical that under the circumstances, the tribe would have regarded Crook’s appearance on the scene as an omen of impending doom. I was so taken with this idea that it led to the title, The Gray Fox. The fox, more so than the wolf, also implies cunning, and that is a characteristic that seems applicable to Crook’s style of warfare.

BGES Blog: During this period, Crook also had to deal with the surge of prospectors and settlers in the Dakota Territory. How did he balance and manage all these dynamic forces?

PM: Throughout his life, Crook had great sympathy for the underdog. On the West Coast, the tribes were not especially warlike and it was the Indians who were the underdogs. The whites were the dominant force. Crook and many soldiers who served in the region during this time resented the settlers and miners as their attacks often provoked an Indian backlash that the Army then had to suppress.

In the Black Hills, before the Great Sioux War, the situation was more ambiguous. Though Crook sympathized with the Indians whose lands the miners and settlers invaded, he regarded the latter as poor, hardworking individuals who led a hardscrabble existence and experienced great danger to lift themselves out of poverty and provide for their families. As such, he saw a need to treat them fairly and sympathetically. However, he was a soldier, first and foremost, and was under orders to remove them from the Hills. Failure to do so, he knew, would result in war and possibly many civilian deaths. He also believed that a takeover by the government of the Black Hills was inevitable. So he carried out his orders, expelling the miners, but did so as humanely as possible, promising them that their claims would be honored at a later date. In the end, most of the miners regarded him as a friend.

BGES Blog: The final volume, An Honest Enemy, George Crook and the Struggle for Indian Rights, covers the last years of Crook’s life, including the Standing Bear case, his campaigns against Geronimo, and his final maturing as an advocate for Indian right. It was released in the spring of 2020. How did it feel to finish such a time-consuming and ambitious project?

PM: I had been researching and writing about Crook for almost 20 years. During that time, it was a major part of my life. I traveled extensively in the United States visiting sites related to Crook’s life and career, read widely on the history of the Western Frontier, attended conferences, and made several friends among historians and history buffs who were interested in Western history. Thus, I greeted completion of the work with mixed feelings. Naturally, I did feel relief at being able to complete this extensive project. On the other hand, finishing it left a big hole in my life. But I guess writers are lucky. There is always the next book. In my case, I am writing a new work about a New England whaling captain and learning all about the early history of whaling in the process.

BGES Blog: An Honest Enemy takes a hard look at Crook’s struggle to reconcile his role as a military officer against his humanitarian instincts and the plight of Native Americans. How did that play out?

PM: From his first assignment on the West Coast, Crook’s attitude toward Native Americans evolved from an initial contemptuous view of Indians typical of most white Americans of the time to an enlightened understanding of them as fellow human beings, deserving of justice and equal treatment. It was an understanding that developed as his knowledge of Indian customs and folkways deepened as well as through his friendship with Indians with whom he hunted and whom he worked with as scouts and warriors.

Crook reluctantly accepted the government’s policy of placing Indians on the reservation—a more palatable solution to the issue than the extermination preferred by many other whites at the time, and believing it would protect them from white Indian haters and thieves. Yet once on the reservation, he fought consistently for their fair treatment, battling corrupt politicians and Indian agents to secure good lands for them and ensure that their reservation boundaries were respected by local whites (and that they received sufficient rations).

Crook’s ultimate solution to the so-called Indian Problem was assimilation. To further that goal, he worked to secure for Indians equal treatment under the law as demonstrated by the landmark case, Standing Bear vs. Crook. He also became one of the first to call for giving Indians the right to vote. His involvement reached a peak in the latter years with his fight to liberate the Chiricahuas from imprisonment after they had surrendered to General Miles after the Geronimo campaign. That fight and his role in trying to ameliorate the hardships connected with the government’s dismemberment of the Great Sioux Reservation were doomed to failure, not only because of his premature death but because they ran counter to prevailing political and public opinion. That, to me, is the profound tragedy of Crook’s life, a decent and courageous man whose struggle to win a place for Native Americans in the country that used to be their own was crushed by the dominant political and social culture in which he lived.

BGES Blog: Crook seemed to spend a good part of his career fighting against the establishment. Where do you think he would stand in today’s world of political division? How would he view our state of affairs?

PM: This is a very provocative question and one that may be colored by my own views of the current situation. But I will try and be as objective as I can be. Crook was largely apolitical. Before the Civil War, he had no political (or religious) affiliation, being, I believe, distrustful of institutions, and being profoundly imbued with the military’s subservience to civilian authority. He took no position on slavery—he knew few if any black people, but he believed very strongly in the Union and so became a loyal supporter of Lincoln and later of Republican presidents, several of whom were officers in the war and one, Hayes, a close friend.

Even with respect to Indian policy, only during the last decade of his career did Crook depart from the chain of command when he raised objections to particular government actions or policies. At the end of his life, however, he departed from this stance and took a moral stand, speaking out publicly on the inequities he observed through newspapers and humanitarian groups. In one case, he even resorted to subterfuge to achieve his ends, allowing himself to be sued in the Standing Bear case as a means to secure the rights of the Ponca tribe.

At the bottom, except for his efforts to secure equity for the Indians during the last decade of his career, Crook was a professional soldier and adhered to the chain of command. Though he believed that the Army rather than the Interior Department should administer Indian affairs, he accepted civilian supremacy in policymaking. Though he never hesitated to criticize his fellow officers, including his superiors, in private conversation, I never saw any reference to the presidents he served under, though his aide John Bourke was not similarly constrained. (He found Grover Cleveland to be morally bankrupt.) On the other hand, Crook had exceptionally high standards of personal integrity and was intolerant of liars, bullies, and braggarts.

Balancing his professionalism with his personal tastes and based on an almost 20-year study of his character, it is my opinion that if the older, mature, Crook were alive today, he would probably endorse the views expressed by General Mattis over these past few years, months, and weeks.

Here are three that stand out:

“Donald Trump is the first president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people—does not even pretend to try. Instead, he tries to divide us. We are witnessing the consequences of three years of this deliberate effort. We are witnessing the consequences of three years without mature leadership.”

“We know that we are better than the abuse of executive authority that we witnessed in Lafayette Square. We must reject and hold accountable those in office who would make a mockery of our Constitution. At the same time, we must remember Lincoln’s “better angels,” and listen to them, as we work to unite.

“Only by adopting a new path—which means, in truth, returning to the original path of our founding ideals—will we again be a country admired and respected at home and abroad.”

BGES Blog: Thanks so much, Paul.

You must be logged in to post a comment.