The Night the War Was Lost

By Charles L. Dufour (Doubleday and Company, 1960, 427 pages)

It is always a delight to pick up a book that has been on your shelves for years, and which you had never looked at twice, and find it is a diamond in the rough. That is my honest sensation after finishing Charles Dufour’s The Night the War Was Lost. Indeed, the book is a part of my legacy and I did not realize it. Although it sat on the shelf, I hadn’t looked at the dust jacket or the subtitle on the cover: The extraordinary events which led up to Farragut’s sweep of the Mississippi and capture of New Orleans. Although being a native of New Orleans and having conducted several tours of the campaign and occupation of New Orleans, this book had never crossed my radar, but, now that I have read it—wow, my cup overflows. I could picture each scenario he narrates and know precisely where the story is told from. The next tour …

It is always a delight to pick up a book that has been on your shelves for years, and which you had never looked at twice, and find it is a diamond in the rough. That is my honest sensation after finishing Charles Dufour’s The Night the War Was Lost. Indeed, the book is a part of my legacy and I did not realize it. Although it sat on the shelf, I hadn’t looked at the dust jacket or the subtitle on the cover: The extraordinary events which led up to Farragut’s sweep of the Mississippi and capture of New Orleans. Although being a native of New Orleans and having conducted several tours of the campaign and occupation of New Orleans, this book had never crossed my radar, but, now that I have read it—wow, my cup overflows. I could picture each scenario he narrates and know precisely where the story is told from. The next tour …

As many of you may know, I am a native of New Orleans. My very earliest awareness of the Civil War goes from 1962 through 1965 as I visited my Grandpa Karl and Grannie Saleeby (mom’s parents) on road trips in Algiers. Both were literate and well aware of the community goings-on—the morning newspaper, The Times-Picayune, and the evening daily, The States Item, were always either in the den or on the kitchen table. I was interested in history and with the centennial of the Civil War underway, Dufour was an editor for both newspapers. Features commemorating the 100th-anniversary events in and around Louisiana were regularly presented. Grandpa had the American Heritage book The Civil War written by Bruce Catton and both National Geographic and Life magazines were running features. All were available to me. What I could not know at the time was that Dufour was the author of many of the articles I was reading. Grandpa willingly took me to the sites. I was hooked. So how cool is it to read Dufour’s magnum opus on the Crescent City?

Dufour’s narrative style is a page-turner. I never found myself looking for an “off-ramp” to take a break, and whenever I came to a chapter break, it was not an issue of putting the book down until later but rather, “How many pages are the next chapter” (I read about 25 pages an hour) and “Should I read it now?” As a result, I finished the book three weeks earlier than I had planned, setting aside other equally interesting books that I was simultaneously reading—finishing with a flourish knocking out the final four chapters before flying home from a road trip. That was six days ago, and I am still juiced by the experience.

The story is perhaps overlooked by many historians who are fixed on the campaigns and the sufferings of the Confederacy in the upper south in Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, and Mississippi. It is natural—indeed, a geographic progression from North to South—that is where the aggressors were coming from, and that is where Gen. Albert Sydney Johnston had built a paper-thin line of resistance. Inexplicably, the core Deep South states that formed the initial Confederacy knew of and yet ignored the South’s largest city and its most prosperous economic engine. New Orleans had been a city of international significance since before the Louisiana Purchase more than 50 years earlier.

New Orleans had foreign envoys and international banks, wharves, factories teeming with goods, shipyards, and the United States Mint. Northern trade moved down the mighty Mississippi from tributary rivers like the Ohio and Red—Lincoln had made a trip down the river; Mark Twain would write about life on the Mississippi. The Natchez Trace was populated by traders returning from New Orleans to pick up new cargos. Opulent plantation homes managed farm and agricultural systems that delivered cash crops such as cotton, tobacco, and sugar cane. Thousands of enslaved persons worked the fields producing the raw goods that would flow to the world. Military ships of foreign nations were welcomed to her docks, and gay party seasons such as the Mardi Gras contributed to the decadence of the city. Within the city, the river trade supported houses of easy virtue and the bawdy life of the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) adjacent to the stately townhomes of the Garden District. New Orleans was then and is today a city of importance and fun. So why was it lost so easily?

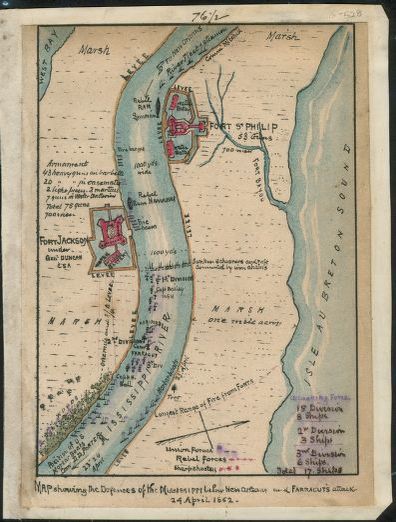

Dufour is disciplined in his narrative. He tells you of the city and the people who were important. He tells you about the city governance and the response of the city to the Confederacy. He describes an arrogant apathy that would infest the salons of the city and leave it dramatically unprepared when the crisis came. I liken it to the city’s response to hurricane preparation—a city in a bowl protected by incomplete levees, with plans it had never practiced and an indifferent leadership more interested in “letting the good times roll” than is sound governance—and then Katrina came. Well, in 1862, Farragut came. The city had substantial but undermanned fortifications. The British had given national purpose to defenses and New Orleans had its share: Forts St. Philip and Jackson stood along the lower Mississippi. Along Lake Borgne, Forts Pike and Macomb covered Chef Menture and the Rigolettes passes into Lake Pontchartrain. Fort Livingston covered Barataria Bay, where the Lafitte Brothers had operated smuggling operations 40 years earlier.

This is a robust narrative that leaves you shaking your head. You can see the train wreck coming, and yet from your comfortable chair, you are unable to prevent it. You are watching the divergence of resources from the city, both soldiers and materials; the selection of decrepit leaders like David Twiggs and a northern transplant, Mansfield Lovell; an uninspired and ineffective ship-building program to deny Lovell the means of defense; and the failure of the civil authorities, from President Davis to Secretary Mallory to Governor Moore to Mayor Monroe.

There are heroes from Dufour’s perspective. He thinks Lovell gets a raw deal, and he thinks Commodore Hollins could have coordinated naval affairs and Gen. Johnson Duncan in command of the lower Mississippi. All were capable. However, this is a story of Farragut, David Porter, and only tangentially Benjamin Butler. The drama of the build-up and the operations to get his fleet over the bar and assembled at Head of Passes, the encounter with the Manassas and “Fire Rafts,” the evaluation of the defenses, the mortar fleet, the decision to pass the forts between 2 AM and dawn, and the vicious fight beyond the forts with the ram Manassas and floating battery Louisiana, the negotiations between Farragut and Monroe, and the mutiny at Fort Jackson all create a rich and robust narrative that leaves you fulfilled and much smarter than when you first picked up the book.

In the end, you may seriously consider if this was indeed “the night the war was lost?”

You must be logged in to post a comment.