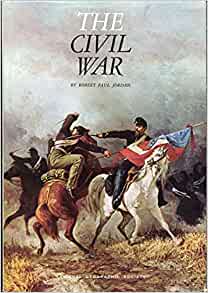

The Civil War

By Robert Paul Jordan (National Geographic Society, 1969)

It has been said a picture is worth a thousand words. If that is so, then Robert Jordan’s book is War and Peace. It was written as a survey reflection on the Civil War amid a country torn apart by antiwar riots, political discourse that is convulsed with racial unrest. Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King have been assassinated, Lyndon Johnson has withdrawn from reelection, and political retread Republican Richard Nixon is the newly elected president. Elected on the promise to end an unpopular and increasingly costly war in which conscription, draft-dodging, and congressional hostility have all consumed the country.

It has been said a picture is worth a thousand words. If that is so, then Robert Jordan’s book is War and Peace. It was written as a survey reflection on the Civil War amid a country torn apart by antiwar riots, political discourse that is convulsed with racial unrest. Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King have been assassinated, Lyndon Johnson has withdrawn from reelection, and political retread Republican Richard Nixon is the newly elected president. Elected on the promise to end an unpopular and increasingly costly war in which conscription, draft-dodging, and congressional hostility have all consumed the country.

The centennial of the Civil War was barely four years in the past. It had been controversial—plagued with cross-currents of a segregated and very torn society. The Voter Rights Act and other civil rights acts had spurred ugly and emotional responses to the disruption of a society in which Brown versus the Board of Education had pried open a door that divides the American experience between Whites and Blacks. I lived that for two years in Mississippi. So why this book?

National Geographic Society was a microcosm of America’s reverence for the Civil War and other American events. Nat Geo had done a multi-issue survey of the War a hundred years later—featured issues in its iconic magazine in 1961, 1963, and 1965. A few years later they did an issue on the Underground Railroad—perhaps in recognition of the emerging interest in civil rights.

Author Robert Jordan was a World War II veteran who entered the U.S. Army in 1942 after interrupting his undergraduate studies at Marquette University. Following his discharge in 1945, he accepted a job at the Washington Post and he progressed from copy boy through reporter and then up to editorial duties. He completed his undergraduate studies at the George Washington University in 1947. Sixteen years later, the now highly experienced Jordan joined the National Geographic Society in 1962. As Assistant Senior Editor for NGS and with military experience, he was a perfect selection for the Society’s introspective look into the legacy of the Civil War. There are numerous pictures of Jordan with his family at all the primary sites, that, combined with my knowledge of the time required to bring a book to print, suggests this book likely started immediately after the Centennial in 1965 and was headed to layout and finalization by late 1967—keep that and contemporary events in mind when considering the book. Jordan passed away in 2006 at the age of 84.

Author Robert Jordan was a World War II veteran who entered the U.S. Army in 1942 after interrupting his undergraduate studies at Marquette University. Following his discharge in 1945, he accepted a job at the Washington Post and he progressed from copy boy through reporter and then up to editorial duties. He completed his undergraduate studies at the George Washington University in 1947. Sixteen years later, the now highly experienced Jordan joined the National Geographic Society in 1962. As Assistant Senior Editor for NGS and with military experience, he was a perfect selection for the Society’s introspective look into the legacy of the Civil War. There are numerous pictures of Jordan with his family at all the primary sites, that, combined with my knowledge of the time required to bring a book to print, suggests this book likely started immediately after the Centennial in 1965 and was headed to layout and finalization by late 1967—keep that and contemporary events in mind when considering the book. Jordan passed away in 2006 at the age of 84.

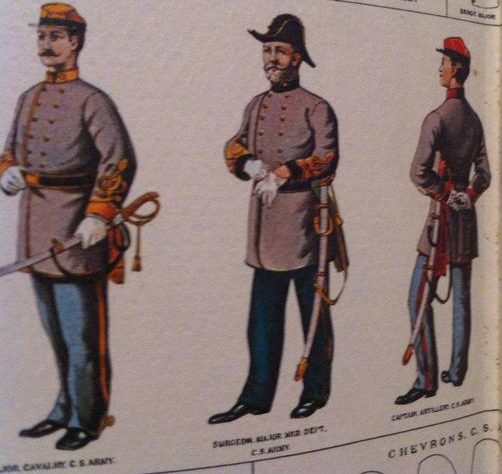

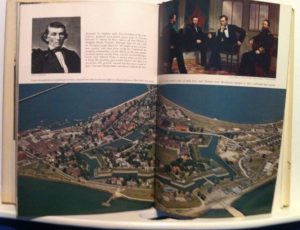

The book is a wonderful and attractive volume with a compelling dust jacket and glossy pages that gives it more the feel of a concise tabletop book. It is lavishly illustrated with artwork of the time, family pictures, and other contemporary photography and maps. The 211 pages, in reality, are no more than perhaps 120 actual pages of narrative. So what is the attraction? Jordan was 45 with a family. He writes a travel log that insightfully surveys the Civil War and its major events organized in six chapters: 1820–1860, then 1861, 1862, 1863, 1864, and 1865. He does not miss much and his summaries are artfully crafted and interspersed with personal interactions with his children who ask probing questions that a child really might and likely asked him. Clearly, he and his wife are engaged in educating their kids in much the same fashion that my parents, and I am sure many of yours, did. It was a different time. The photographs showing the author and his family at places like the Little Round Top, Devils Den, and in the parlor of the Wilmer McLean house at Appomattox are all extremely effective.

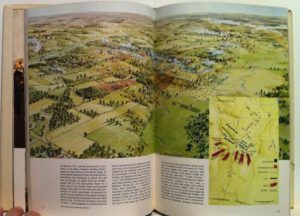

In such a short essay, it is not fair to pick nits nor is it appropriate to question his selection of material. Suffice it to say, as a general history it is more than adequate. I appreciated his interface and apparent collaboration with the National Park Service and some state historians as he visited the sites. With his military background, he does not commit simple mistakes that a beat reporter often does. The powerful editorial presence and resources of the NGS made the book special. Captions for images and artwork are descriptive, maps are attractive, and a very good faith effort to place troops and major movements on a single map are made whole by straightforward descriptions of the flow of the operations in the captions. A concise but comprehensive index helps people look for areas of interest.

In such a short essay, it is not fair to pick nits nor is it appropriate to question his selection of material. Suffice it to say, as a general history it is more than adequate. I appreciated his interface and apparent collaboration with the National Park Service and some state historians as he visited the sites. With his military background, he does not commit simple mistakes that a beat reporter often does. The powerful editorial presence and resources of the NGS made the book special. Captions for images and artwork are descriptive, maps are attractive, and a very good faith effort to place troops and major movements on a single map are made whole by straightforward descriptions of the flow of the operations in the captions. A concise but comprehensive index helps people look for areas of interest.

This book is long out of print—I have the fifth printing of the book in 1982. National Geographic said the print history would suggest that they sold more than 100,000 copies over the life of its print run. I looked for copies and found new copies run between $650 and $875—used copies can be had for less.

I rated this 3 1/2 stars because it is a little breezy in its treatment. Some sixties interpretations would offend some people today. The author holds Lee and the southern heroes in obvious reverence—a very traditional interpretation. He is also a big fan of U.S. Grant. Both Lincoln and Davis have been treated with respect if not admiration. I accept that and note that he is a man who would have known Civil War veterans during the Depression. His admiration for them as a “Greatest Generation” of his time likely rivals the current attitude toward World War Two veterans.

A very useful book, not a hard read, and certainly refreshing at a time there is so much harsh criticism of all things rebellious.

You must be logged in to post a comment.