Hank Koopman wants to correct decades of inaccuracies and revisionism in the various accounts of the two-day battle at Shiloh in April 1862. He has spent 20 years pursuing in-depth research, and he doesn’t mince words. Perhaps his great-great-grandfather’s suffering as a prisoner—he was captured with General Prentiss in the Hornets’ Nest at Shiloh—explains his take-no-prisoners approach and dogged scholarship. He begins by asserting that even the free pamphlet (given out upon request and on the website) that the National Park Service Battlefield Park at Shiloh is flawed.

“There are numerous statements in that pamphlet that are simply false. It should be noted that the park does not treat men who fought in the Hornets’ Nest and were taken prisoner along with Gen. Benjamin Prentiss, as war casualties. If they did, then their numbers wouldn’t work out.” He continues, “The highlights of my Shiloh work contradict Shiloh revisionism so if that is highlighted in an article it would be controversial, but it would be the truth.”

In a few instances, the narrative of history is neither clear-cut, nor well-defined. Even icons like Ulysses S. Grant squinted to remember events. History is concrete until it isn’t. Sometimes it becomes a parlor game of supposition. What if Don Carlos Buell’s arrival had not been delayed? What if General Johnston had survived the lethal shot to his leg? What if Colonel Peabody had not sent out Powell’s early morning patrol? What if P.G.T. Beauregard had not called off the attack. What if, what if?

Grant, who wrote many years later, “‘[Shiloh] has been perhaps less understood, or, to state the case more accurately, more persistently misunderstood, than any other engagement … during the entire rebellion.”

Each officer was required to prepare a full report after each battle. Because Prentiss was imprisoned in the South, he didnot submit his official battle report until November 17, 1862. During his six months of captivity, he was unaware of the death of Peabody, and equally unaware of the disinformation that arose in newspaper accounts of the battle. Koopman suggests strongly that those newspaper claims are false. Finally, 17 years after Shiloh, Prentiss’s unlikely defender was the son of his southern foe, Confederate Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, whose biography of his father refuted the spurious claims against Prentiss in 1879.

Koopman believes that this is what actually happened that day:

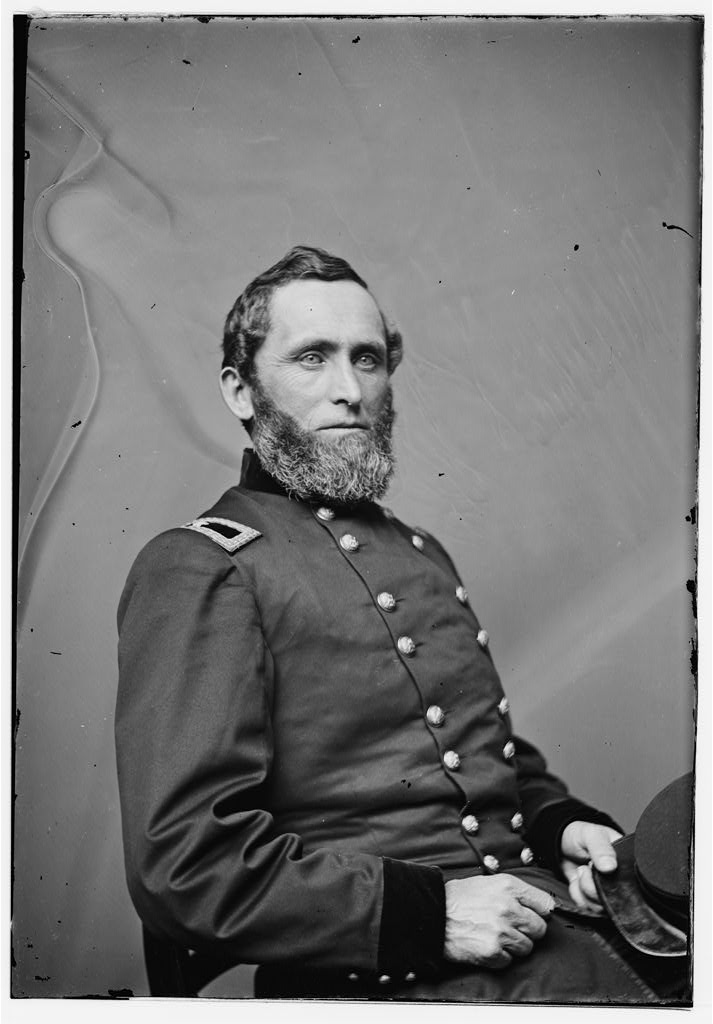

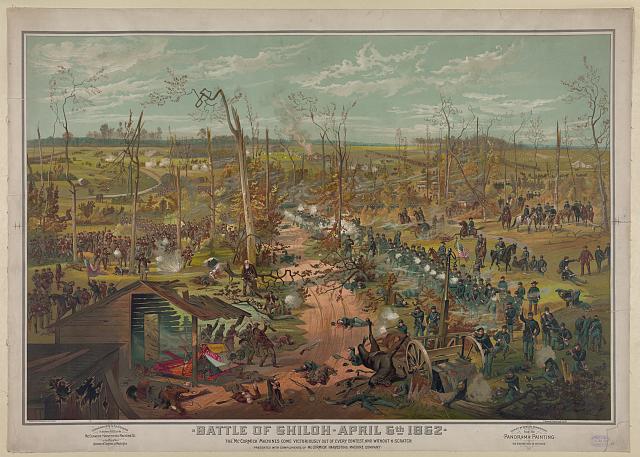

Benjamin Prentiss commanded the 6th Division of Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee on April 6, 1862. Two brigades, a total of 5,400 men, were nearest the Confederate battle lines. Even though close at hand, the Union army was not fully aware that 44,000 Confederate soldiers of the Army of the Mississippi were ready to launch a surprise attack, even with advance intelligence from soldiers at the perimeter of the Union encampment. Prentiss ordered additional pickets and sent patrols to the front. Col. Everett Peabody, under Prentiss command, rode at the head of the first brigade, while Prentiss sent scouts to scour the vicinity for CSA cavalry units. Colonel Peabody ordered patrols to advance beyond the Union pickets. Peabody was searching for information but ended up kickstarting the battle of Shiloh, which violated the do-not-engage directive to Prentiss from the top brass.

According to Koopman: “Major James E. Powell’s patrol gave at least two hours early warning for the Union army and prevented a total surprise.”

Colonel Peabody was subsequently felled in battle, while Prentiss fought on in what became known as “the Hornets’ Nest,” where he and a diminished band of 450 men from his division and 575 men of the 23rd Missouri battled in the Hornets’ Nest along the Sunken Road for seven hours. Gen. Will Wallace, in a final attempt to hold Union ground, was shot and mortally wounded, while General Prentiss surrendered, was captured, and taken prisoner with his remaining men at day’s end. He was released from prison in October 1862, at which time he briefly alluded to Shiloh in a speech in Chicago. In it, he refutes the allegations against himself and the men at the Hornets’ Nest. And then he went silent.

In a letter, Koopman elaborates: “The first published reports of the battle falsely maligned Prentiss and the men captured with him as cowards for having surrendered in the morning rather than in the evening of April 6. This injustice was repeated in many histories written after the war and stuck in the public’s memory for 20 years after the battle during which time Prentiss remained largely silent because he knew what he and his men had done and critics were not worthy of a response.”

In 1882, in an oration at the Burnet House in Cincinnati, Prentiss finally spoke up to exonerate himself and his men. When the Shiloh National Military Park was founded in 1895, Prentiss’s star rose amid narrations of Hornets’ Nest valor, and in part, thanks to Shiloh Park Historian David Wilson Reed, who had also fought in that battle. As a result, Prentiss became a key hero of Shiloh, ostensibly leaving behind the ignominy of implied cowardice. But history is not always kind, nor absolutely accurate. Twentieth-century historians once again leveled accusations against Prentiss, painting a portrait of a soldier who was, in their view, merely his own best press agent. Koopman explains that revisionist historians believe that “Prentiss took credit for sending out the army-saving 3 a.m. patrol when it was Peabody who did it. Revisionists claim it was William H. L. Wallace who defended the Hornets’ Nest, and that Prentiss was inconsequential but talked himself up to being the ‘Hero of Shiloh’ at the expense of Peabody and Wallace.”

In the 1970s, the hero again became the goat. Hank Koopman says a firm “no” to those who have crafted an opposing text of the Hornets’ Nest. He challenges revisionist accounts of Shiloh and backs his assertions with research. The see-saw history of valor juxtaposed with vainglory is hard to fathom. The case for Gen. Benjamin Prentiss will continue to be argued by Mr. Koopman.

Hank Koopman lives in Denver and is a retired civil engineer. He is also an historian, researcher, and author. His book about the critical decisions made at Forts Henry and Donelson will be published by the University of Tennessee Press. His great-great-grandfather fought with the 58th Illinois at Shiloh, was captured in Hell’s Hollow, and suffered a broken arm in prison. Mr. Koopman first visited the Shiloh National Military Park in 2000, which ignited his research on the history of Shiloh.