If you’re not a believer in fate, then Dennis Frye’s amazing life journey may be somewhat lost on you. For the rest of us—including Frye himself—his story is a case study in the compelling power of destiny.

“I agree one thousand percent,” he says.

Frye, a longtime supporter and faculty member for BGES, was slated to host “Stonewall Jackson’s Greatest Victory” at Harpers Ferry in October 2020. (The tour has been rescheduled for July 31 to August 1, 2021.) There is no one more qualified for the job.

As Frye likes to say, he was “born and grew up in Civil War country”—in Maryland during the ’60s and ’70s, just 4 miles from Harpers Ferry and 6 miles as the crow flies from Antietam.

“I would play with grade school friends in the Civil War forts on Maryland Heights,” he recalls. “We didn’t have to imagine history. We lived it.”

His father, John, a draftsman for the state, was known far and wide as the unofficial historian of Washington County, Maryland. His job called on him to research and upgrade land maps for real estate tax purposes, and he quickly gained an encyclopedic knowledge of the area. Frye would accompany his father on tours of Harpers Ferry and other historic sites.

“I marveled at how intently people listened to him,” Frye says. “By the sixth grade, I decided that I would be a historian and a park ranger.”

Frye became a voracious reader, drawn in particular to anything written by James Murfin, who was born in 1929 in nearby Hagerstown in 1929 and authored more than a dozen books and numerous articles about the national parks, including the award-winning The Gleam of Bayonets. He also joined the Youth Conservation Corps, a group of about 50 teenagers dedicated to preserving American history and educating others about it. Just like his father, Frye made a name for himself as an expert on Maryland’s Civil War past. At the age of 15, he became the first YCC member to participate in living history presentations.

“My first job was working in a blacksmith shop,” he remembers proudly.

Meanwhile, Frye continued to learn from the example set by his father. “I never met a stronger advocate for historical preservation than my dad,” he says. “In 1967, he stopped power lines from obscuring views all over Antietam. He was also an original cofounder of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park.”

Those lessons weren’t lost on Frye. He made good on his pledge to work for NPS at Harpers Ferry. And in 1987, he cofounded today’s American Battlefield Trust. He would go on to be ABT’s president for a stint in the 1990s, and later was recognized for his leadership with the Shelby Foote Award and the Nevin-Freeman Award. Frye is also a founding member of the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites. He served as the group’s second executive director.

In 1997, in his role with ABT, Frye oversaw the largest Civil War conference ever, with more than 800 participants in attendance. This also marked his early relationship with BGES.

“The conference was so big that I needed plenty of help,” Frye says. “I had been in discussions with Len Riedel about the synergy between ABT and BGES. I ended up hiring him to serve as the logistics manager for the conference.”

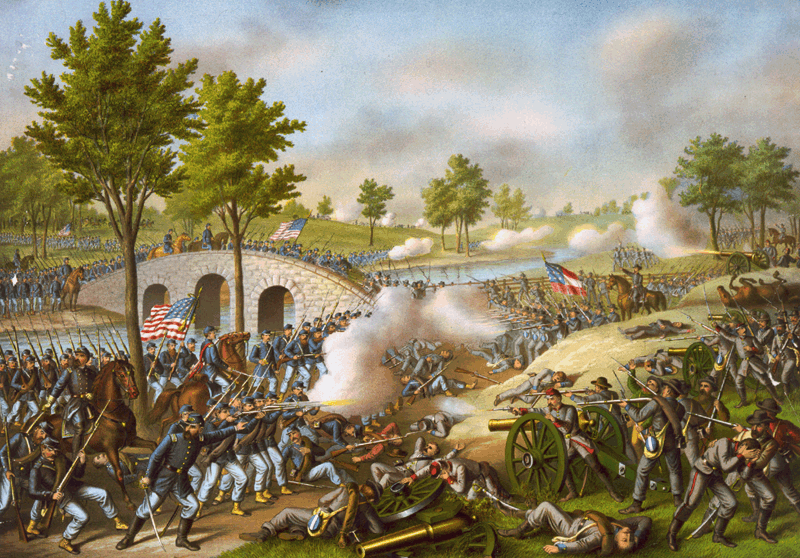

Simultaneously, Frye was busy organizing a reenactment of the Battle of Antietam, part of activities to commemorate the 135th anniversary. He was determined to do it to scale, which meant utilizing some 13,000 reenactors. The event attracted over 100,000 spectators, with proceeds benefitting battlefield preservation.

The Antietam reenactment also helped set the stage for Frye’s Hollywood debut. He had long been a friend and colleague of Ron Maxwell, the writer and director of Gettysburg. When Maxwell decided to move ahead on plans to make the film version of Gods and Generals, he brought Frye on board as a historian and producer. Among other things, Frye was charged with ensuring the accuracy of battle scenes. His one regret? “Due to the film’s PG rating,” he says, “there was not nearly enough blood.”

One day on set, Maxwell made an unexpected offer to Frye. “He asked me if I wanted to be in the movie,” Frye recalls. “I could pick any role, as long it didn’t have too many lines. We agreed that I would play Griffin’s aide.”

Throughout this period, Frye somehow managed to find time to write prodigiously. In all, he has authored 11 books and more than 100 articles on the Civil War. His most recent efforts are Confluence: Harpers Ferry as Destiny and Antietam Shadows: Mystery, Myth & Machination.

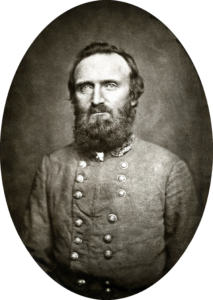

As a historian, Frye feels it’s important to explore all sides of a story. When he first started writing about the Civil War in the 1970s, he found the topic didn’t generate much interest. So he made it his mission to change that. Between the Confederacy and the Union, he never picked favorites, though he did develop a growing fascination with Stonewall Jackson.

Frye’s upcoming BGES tour is in many ways a celebration of his passionate study of the Confederate general. The focus is upon Harpers Ferry during the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Frye calls it “the greatest tactical masterpiece” of Jackson’s career. “It was miraculous that he succeeded,” he says. “Not everyone thinks of the Maryland Campaign in that way, but I’ll prove to you that it’s true.”

One of the reasons this tour is near and dear to Frye’s heart is his connection to ground where it takes place. It’s his home turf, quite literally, and he has always held it in the highest esteem. For example, when Grove Farm in nearby Sharpsburg faced a threat from developers in 1986, Frye stepped in and cofounded Save Historic Antietam Foundation, which helped preserve the property.

Decades later he took on a project with even more personal meaning to him. He and his wife purchased Ambrose Burnside’s post-Antietam headquarters, which hosted Abraham Lincoln after the famous 1862 battle, and went about restoring it as their residence. They still live there today.

“The house required a lot of work,” Frye says. “It was livable when we bought it, but barely. Our goal was to maintain the historical integrity of the entire property.”

That brings us back to where we started this story and where Frye started his: the rural Maryland countryside that saw some of the Civil War’s most momentous milestones.

“The spirit of history is very prevalent here,” he says. “I get chills everyday knowing what occurred on these grounds.”

Life can be that way when fate smiles so fondly on you.

You must be logged in to post a comment.