The BGES Blog never misses an opportunity to talk with Paul Severance. An Army veteran, he is an acknowledged expert on Gettysburg and a living history enthusiast. Severance has hosted several BGES tours, and was originally scheduled to lead another, “A Walking Tour of the Battle of Fredericksburg,” in December—thanks to Covid-19 it’s been rescheduled for December 2021. In the meantime, we recently discussed Fredericksburg and other topics of interest with him.

BGES Blog: Let’s start with some background on you. You served 30 years in the Army. Tell us about your career.

PS: I served in both infantry and aviation units for 23 years and finished up my last seven years as a professor of strategy at the Industrial College of the Armed Forces (ICAF), since renamed the Eisenhower School of National Security and Resource Strategy. Following retirement from active duty, I returned to ICAF as a professor of military science, obtained my Ph.D. from Virginia Tech, and spent an additional 18 years on the faculty, teaching strategy, military strategy and warfare, strategic geography, geography and warfighting, and defense strategy and resourcing.

Since 1995, I served as the director of the Gettysburg Studies Program and have conducted almost 300 “professional” rides at Civil War and WWII battlefields. Coming of age during the centennial of the Civil War, my interest in the American Civil War was piqued by the historical tsunami sweeping across the nation at that time. My first “real” book that I read was Bruce Catton’s This Hallowed Ground in the 6th grade. I’ve been hooked ever since.

BGES Blog: You’re scheduled to guide a new tour for BGES, “A Walking Tour of the Battle of Fredericksburg.” What is your interest in this phase of the Civil War?

PS: Recall that the Army of the Potomac’s Fredericksburg Campaign grew out of the frustration of the authorities in Washington with McClellan’s inactivity following the Battle of Antietam. (We can argue whether it was a Union victory or a draw.) Recall also that Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, but both the domestic political and international diplomatic needed a clear-cut military victory to support and succor Lincoln’s strategic political aims. Otherwise, the proclamation would be viewed as a desperate act of the Executive trying to salvage a lost cause. In this particular respect, we need to remember that Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia, with the exception of Antietam, have been on a roll. Indeed the only positive achievements for the Union have come from the Western Theater, and they were few and far between.

As we know, McClellan is cashiered, Burnside is installed, and the pressure immediately mounts for another major offensive campaign and a definitive (if not decisive) victory—in the winter, no less, when most armies have historically gone into winter quarters because of the immense environmental, operational, and logistics difficulties occasioned by winter campaigns. Taken as a whole, then, the study of a winter campaign intrigues me (especially given my two years in Alaska as an infantry officer), especially when viewed in the light of national strategic imperatives.

As many members of our Society know from their military experience, winter warfare is not a sport for the weak of heart (or physique). It’s tough sledding (excuse the pun) on a massive scale. Pursuing a different branch, being a “closet geographer,” the geographic (to include climate and weather) and topographic dimensions of the campaign and battle (including the fateful “Mud March” in January 1863) have always drawn my attention and inquiry.

Scoping down to the tactical dimension, the Battle of Fredericksburg witnessed the first major river crossing by military forces under fire in U.S. history, as well as the first relevant experience in fighting in towns and built-up areas—door-to-door, house-to-house, street-to street—what we refer to today as military operations in urban terrain (MOUT). Both of these latter circumstances demanded rapid adaptation by the Army of Potomac, which it did.

Finally, Fredericksburg was the first major battle that directly and severely affected the 5,000-odd civilians who lived in and around the town. The pitiful exodus of the town’s population and the severe damage to the town due to artillery and close combat and uncontrolled looting and pillage by the Army of the Potomac still resonate in the region to this day. In short, lots of new mother lodes to be exploited from November 1862 to late January 1863 when Burnside is relieved of command after his infamous Mud March.

BGES Blog: You refer to Fredericksburg as “one of the American military’s most tragic episodes.” What made it so?

PS: Where do you want to start? The massive waste in human life—almost 13,000 for the Army of the Potomac and some 5,000 casualties on the Confederate side of the ledger. Consider also the wanton destruction of the town and civilian property and the sorrowful evacuation of civilians from a combat zone that followed. We must also consider the insidious impact of internal political loyalties, cliques, and sinister machinations with the Army of the Potomac that virtually doomed Burnside and the Army of the Potomac to abysmal failure from the start.

From a different, but arguably useful perspective, one of my “research quirks” as I study military campaigns and battles is to harvest “descriptions” of the event by participants and observers both near and distant. You could fill a small book with these arguably emotional descriptors for Fredericksburg, some emerging mere days after the battle, some emerging weeks later as interested observers—ranging from soldiers’ private diaries and letters home to pompous pronunciations for public consumption by biased newspaper correspondents and editors to testimony by Federal officers before the Congressional Joint committee on the Conduct of the War.

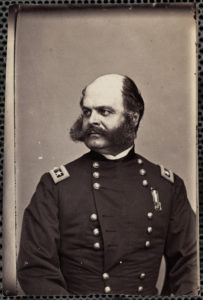

BGES Blog: What is your assessment of Burnside as a leader?

PS: Clearly, “Sides” was unsuccessful in the extreme. Not surprisingly, history has not been kind to Ambrose Burnside, citing him as inept, overwhelmed, and clearly unqualified by high command. Viewed in the aggregate, in his short tenure of command of nine weeks (the shortest of any commander of the Army of the Potomac), Burnside experienced four unsuccessful operations, from the initial bridging operations to the debacle history records as the “Mud March.” Conversely—and to his credit—Burnside himself recognized and admitted that he was unqualified to command an Army. Indeed, he tried to decline command twice, but only acceded to the appointment when he realized “Fighting Joe” Hooker would assume command in his stead.

On the other hand, more recent scholarship has been somewhat gentler on and kinder to Burnside. I tend to fall into this camp, but not very deeply. To his credit, Burnside’s final operational approach to operate along the Rappahannock and tie his logistics to the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac railroad and water supply lines of the Potomac to Aquia Creek was pretty solid and had the potential to interpose the Army of the Potomac between Lee and Richmond. Once his plan was approved in Washington, Burnside moved with alacrity and actually beat Lee (Longstreet’s Corps) to Fredericksburg, with Sumner’s II Corps arriving on November 17. The road to Richmond—for all intents and purposes—was open! However, in the finest traditions of the tyranny of logistics, the infamous pontoons that were necessary to bridge the river had not arrived. In fact, the first batch of engineers (50th New York) and pontoons did not reach the river until November 25; Sumner and Burnside cooled their heels on the east bank of the Rappahannock.

More critically, the delay in bridging gave Lee the time he needed to move Longstreet to Fredericksburg and recall Jackson from the Shenandoah Valley. By the time all the cursed pontoons arrived, Lee had constructed an impressive 32-mile defensive position from Banks Ford in the northwest to Port Royal in the south.

Burnside also had to contend with a chain of command that was highly politically motivated and driven by pro-McClellan and anti-McClellan cliques. Burnside was arguably NOT a McClellan man and unfortunately did not enjoy the complete trust and confidence, much less the willing support of most of the anti-McClellan (Republican) faction of the army. Leadership—other than or purging or replacing the bad actors—can only take you so far before you become essentially powerless to command. It’s a fascinating study in its own right, especially given the cherished anti-political principles of American Civil-Military Relations. Lincoln once observed that you have to work with the tools that you are given. General officers like Reynolds and Meade aside, Burnside had a lousy toolbox.

BGES Blog: Fredericksburg was the largest battle of the Civil War, involving nearly 200,000 combatants. Did the large number of troops and size of the battle affect how it was fought?

PS: That’s an interesting question, especially given the experience of both armies prior to Fredericksburg with respect to percentages of combat forces actually committed to the grinder. First Manassas and Antietam immediately come to mind in terms of under-employment of combat capabilities. As I ponder the question further, I think perhaps that an equally compelling question might take the form of: What forcing factors (externalities) influenced the number of troops committed to battle and shaped the eventual scope of the battle?

Let’s start with organization for combat. As we know, Burnside created an extra layer of command by forming three “Grand Divisions” consisting of two corps each. To his credit, Burnside delegated a number of major command responsibilities to these three commanders. Unfortunately, given the loyalty and self-serving motives of at least two of these commanders, Burnside effectively removed himself from more proximate and direct command (leadership) of his army and the management of the battle. By the same token, we must recall that even at this point in the war most commanders on both sides had not commanded large bodies of troops during the constabulary operations in the West after the Mexican War. Even the venerated Robert E. Lee had only commanded a force approaching 300 prewar.

Remember also that the Regular Army was capped at just over 42,000 men; the rest of the units fighting this high technological-high lethality war were all volunteers or draftees. Beyond the numbers, add to that the sheer geographic scope of the battlefield (almost a 7-mile front) running from river north of the town to Hamilton’s Crossing in the south, as well as a daunting array of obstacles and barriers created by the mighty Rappahannock, canal ditches on the plains above the town, mud (and more mud), limited (and confusing) roads, railroad right-of-ways transecting the battlefield, and of course the built-up areas of the town.

As a final coda, Lee was in a stationary defensive position and essentially engaged most of troops at some point in the battle. Burnside—on the offensive—has to stage his troops east of the Rappahannock, and trust his three major subordinates to cross a river (under fire) and conduct movement and maneuver encumbered by the freezing weather and the natural and man-made obstacles and barriers enumerated above. It’s no wonder Burnside could not bring all his combat power to bear on December 13.

BGES Blog: You’ve done many other tours for BGES, including “A Military Perspective of the Gettysburg Campaign” in 2019. How does the Fredericksburg tour compare?

PS: Fredericksburg is (as is Antietam), in many ways, an “easy” battle to study and evaluate in the sense that it is more or less a linear battle, running south to north with definitive phases that only marginally overlap and that essentially unfold over a single day. Additionally, the battle was characterized by sequential arrival of units to the area of operations, careful planning on both sides, and deliberate, sequenced operations on the Union side that largely unfold according to the planning conducted by Burnside and his staff. As a mirror image of Gettysburg, the Army of the Potomac is the aggressor; the Army of Northern Virginia the defender.

The Battle of Fredericksburg is also well-defined geographically in terms of positions, lines of battles, obstacles and barriers, etc. Gettysburg, on the other hand, is a three-day affair that grows from a classic meeting engagement with engagements occurring on opposite ends of the battlefield simultaneously. The Army of Northern Virginia is on the attack, committing forces as the unfolding situation dictates while the Army of the Potomac is largely in strong, fixed defensive positions. Although not widely considered or discussed, both campaigns and battles are superb studies of the impact of logistics of combat operations. Likewise, both battles offer a plethora of leadership and decision-making case studies that can be of incredible value to the aspiring strategist and/or military historian.

One additional aspect of Fredericksburg that captures my interest is that the Confederate victory at Fredericksburg supposedly imprinted on Longstreet’s brain the implicit value of a strong defensive position as he watched his troops mow down repeated Union brigade-level attacks in front of the Stone Wall and Sunken Road on Marye’s Heights. As most serious students of the Civil War know, this enculturation of the value of the defense re-emerges at Gettysburg where Lee and Longstreet disagree on future courses of action after Day 1 (“command dissonance”) and Longstreet becomes a truculent and petulant subordinate for the remainder of the battle that many scholars and observers maintain doomed Lee’s offensive operations at Gettysburg to failure.

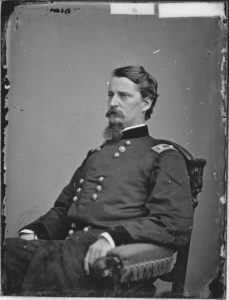

BGES Blog: You’re a living historian, regularly playing Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock. What do you enjoy about this role? Does it at all inform how you conduct your tours?

PS: My persona as Hancock actually has two dimensions. The first derives from my role as Historian and Head Docent at the Lincoln Assassination Conspirators Restored Trail Courtroom at Fort McNair in Washington. Not many people know that Hancock was commanding the Middle Military Division (which included Washington) with headquarters at Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley. Stanton summoned Hancock to Washington on April 16 to superintend the trial, provide security, and ensure the sentences of the tribunal were expeditiously carried out. Stanton fully expected all eight conspirators to be found guilty and hanged without delay to send a message to any other Confederate diehards who might have insurgent warfare on their mind in the wake of Lee’s surrender on April 14. In this “role,” I find I can provide a modicum of objectivity and historical fidelity by relating the course of events surrounding the trial in the first-person tense. Unfortunately, my ubiquitous (some say “inappropriate”) sense of humor and penchant for storytelling unhinge my persona as Hancock.

The second dimension is portraying Hancock on the battlefield at Gettysburg and engaging with visitors about Hancock’s incredible leadership, decision-making, and performance on all three days of the battle of Gettysburg. I do this at the Pennsylvania Monument in the center of the Union line on Days 2 and 3 and it’s great fun to bring Hancock to life in this particular setting.