Hope & Glory: Essays on the Legacy of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment

Edited by Martin Blatt, Thomas J. Brown, and Donald Yacovone, foreword by Gen. Colin Powell (University of Massachusetts Press, 2001)

They were not the first, but they were arguably the most famous black regiment in United States military history. The 54th Massachusetts Infantry was immortalized in popular culture by the 1989 movie Glory starring Matthew Broderick, Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman, and others. The movie was generally accurate in facts, but it was the powerful story, the personalities, and the dramatic assault at Battery Wagner, a site that is mostly submerged, on the barrier island named Morris just south of Fort Sumter, that make it so memorable. The assault which failed resulted in the deaths of the white commander, Colonel Shaw, and a number of his black soldiers. The southerners meaning to demean him buried him in the harsh language of the time “with his niggers.” When northern agents sought to exhume Shaw’s body, his parents, who were rabid abolitionists, objected, saying that there was no more sacred or appropriate spot for him to rest than with the men he led to immortality, and so there he and his soldiers lay beneath the waves of the Atlantic Ocean.

The period after the war created tremendous memorials on both sides. In Boston, a commission with Augustus Saint-Gaudens took years to complete, and when unveiled in 1897 on Boston Common across from the Massachusetts State House, it was quickly recognized as an enduring work of art. In the summer of 2020 the monument, depicting the white Shaw riding at the head of his black troops, who are leaning forward into battle and clearly subordinate to him, was defaced by vandals as part of a general antipathy toward anything and anyone Civil War. Even Abraham Lincoln is being removed from public display because of the slavery symbolism associated with his monument in Boston. Will this eventually come to Saint-Gaudens? Time will tell.

I have seen the monument as have many readers, and I didn’t spend as much time studying it as I should have. This book returned me to that moment and monument. The book is a series of essays developed and presented for the 100th anniversary of the dedication of the monument. Two remarkable aspects of the ceremony of rededication were the presence of a large contingent of black reenactors led by a token white officer that were passing in review in front of the highest ranking black military man in American history, Gen. Colin Powell. Today, 24 years after that event, another black four-star general is the United States Secretary of Defense. A black man has been elected president and reelected, and a black woman has been elected as the first woman to be either president or vice president. Mission accomplished.

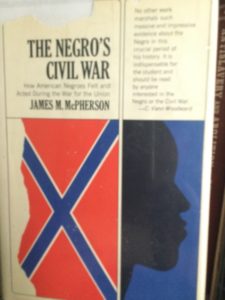

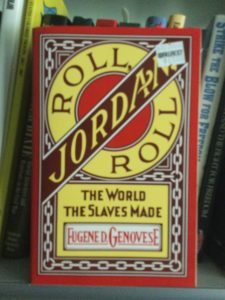

So why is this book important? Frankly, it sat on my bookshelf for years. I have read essay books before, and they generally are yawners. And, while I have a library of 5,000-plus books, I have read perhaps 1,200 of them. Among them are two shelves devoted to African-American studies. I have not read more than two or three of those volumes. I also find, unlike Shaw’s parents, I have segregated the books I have on him—his letters, etc.—and placed them in the Union officers section that starts with Grant and holds considerable works—every one about a white officer. My library by design is thematically segregated—hummmm. Of course, in the battle section, I have the narratives of Fort Pillow, Port Hudson, Olustee, the Crater, and other engagements in which black soldiers fought, but as a whole, the genre of works that includes James McPherson’s early work The Negro in the Civil War sits alone and unread.

So what is my point? This book is the front door to an entire set of intellectual and social dialogue. Among 15 essays, one is written by the nation’s top scholar on race and memory; he is at Yale, a northern perspective. Tom Brown is a professor at the University of South Carolina, perhaps the most radical state in the South—and the state where 54th earned its Glory fame. Certainly diverse geography. Yet if you read the book and are impressed that it is either good or bad, interesting or boring, has too much of a military or civilian slant, or perhaps is drifting too much into fine arts or literature, be patient and hold each essay up to the light and, just as a prism gives you diversity from the split light, you will be enlightened. If you are a deep and insightful person, you will find much to chew on both intellectually and ethically because you can see where we never emerged from the core issues at stake over slavery and desegregation. Equal opportunity makes for good electioneering and slogans, but in practice can be a very difficult construct to ensure—clearly an Ideal, subject to the friction of the human experience and the actors affected by it.

If this critique is difficult to read, it should be, because the scholars really challenge you to consider issues of equality and equity, right and wrong, privilege versus prejudice, and moral versus amoral (not immoral)—all constructs that cut both ways. The book is divided into sections—a bit over 70 pages and four essays on the unit and the 19th-century world of the black man and his denied manhood. Another six essays and 90 pages deal with legacy and, indeed, fame or infamy. Finally, 80 pages and five essays look forward to the challenge of renewal of the immortality achieved on battlefields across the world. Powell’s introduction sets a challenge to us and gives us a contemporary pathway to consider, one that unfortunately in the experience of the past 24 years, since it was delivered, suggests that we owe ourselves candidly a pretty poor grade.

Artistically, in song and in script, we are challenged to use the Saint-Gaudens monument for the purpose which the sculptor intended. There is purpose in the design and individuality of Shaw and each of the black soldiers he towered above. It is a work that emerges from the bronze and reaches out with a message he intended to deliver at the turn of the 20th century. It seems to me that the vandals and new “Woke” mob don’t know enough to know when a work is instructive and therefore useful, and when it is just a target of hate and rage.

Recently, a museum in New York City opted to remove an equestrian statue of Theodore Roosevelt because of the subordinate positions of an American Indian and a man of color. His descendants concurred. Yet last week on tour I visited Theodore Roosevelt National Park and viewed the Badlands and multiple monuments that he created from nature and the environment he lived in. I saw his bust on Mount Rushmore as well as an emerging bust of Crazy Horse from the side of a mountain not so far away. I also saw a heroic monument of Martin Luther King emerging out of a block of granite on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

About 20 years ago, the late great Ed Bearss was guest of honor at a symposium directed at him. His friends came from far and near to talk for 20 minutes on a topic of their choosing and to socialize. There were historians and reenactors—such as Walt Wittman. Ed was nearly 80 years old and he sat through every one of the talks. Afterward. he told me that he got something from every talk given. There is something to be gained by an attitude of endless learning.

This book sat on my shelf for at least 10 years, and yet there it was to instruct and inspire me. Blue and Gray will make some educational adjustments in the coming months and years to take more of that story off the shelves and open a discussion. It is an essential lesson of our war, and we generally ignore it or misunderstand the full power of the moment then and the implications today.

I highly recommend this book as a sobering values check as to why we really study the Civil War.