![]()

The life of a career National Park Service professional, seasonal or full-time, is a transient one, nomadic in nature. The novelist Nevada Barr, herself a former Park Service ranger, has made an alternative career of fictionally documenting the rootless odysseys of rangers, historians, and superintendents. Neil Mangum is one such Park Service denizen, who has been in pursuit of his boyhood fascination George Armstrong Custer for decades.

Mangum grew up in Petersburg, Virginia, near the expansive battlefields of the Crater, City Point, and the Blandford Church at Hopewell, with its authentic Louis Comfort Tiffany stained-glass windows that depict the states of the Confederacy as so many 19th-century apostles. In short, Petersburg is a place in time, steeped in tragic U.S. history, blood still infused in the soil. Like any Park Service postulant, Mangum was content for a time to work in his hometown at the Petersburg Battlefield Park, hoping to use it as a stepping stone to his one true ambition: Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in Montana. The last stand of his idol, Custer. Alas, the Park Service had other ideas. Neil and his wife packed their car multiple times, moving on to Desoto National Memorial Park in Florida, then to the Ozark National Scenic Riverways in Missouri. Perhaps three times was the charm, or the last straw. Neil and his wife headed for Montana, ostensibly on vacation, where Neil by happenstance arrived on the doorstep of Little Bighorn. He introduced himself to the superintendent, going directly to the top, bypassing middle management. To his shock and surprise, the gambit worked. The Mangums uprooted themselves yet again, and this time, they settled in for nine years![]()

History has a way of teaching us things we sometimes don’t want to learn, or we simply trip over en route elsewhere. The shadow of George Armstrong Custer, the dashing Union officer with flowing hair and luxuriant mustaches, loomed large in Mangum’s life, his hero and laudable martyr. Living among the ghosts at Little Bighorn National Battlefield Monument offered Neil new lessons, which became interpretive truths. “From hero to goat to villain” is how Neil describes the odyssey of Custer. A generation of schoolchildren read and absorbed textbooks that told the famous story of that furnace-like day in June 1876 at Little Bighorn. Custer, outnumbered, was painted repeatedly as the unquestionable paladin and lost champion. Not so fast, says Mangum. Living and working in the vast, big sky country of Montana, Mangum’s mind filed and organized questions. Unlike historians that preceded him, Neil did what had never, or rarely, been done. He talked with the Native tribes who lived around him as his neighbors and friends.![]()

![]()

![]()

Neil draws a very different picture of the lead-up to and eventual result of that horrific battlefield fiasco. The Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho tribes spent brutal Montana winters huddled together on designated reservations. In the Spring months, the tribes traveled fluidly on and off reservation lands. Simultaneously, the population of the United States remained in the grip of a secular religious fervor for westward expansion. Manifest Destiny. Maybe the promise of a fresh start served to bind up the wounds of recent civil strife and assuaged the grief of loss. As a result of this urge to “Go West, young man” and in the wake of unspeakable destruction wrought by Andrew Jackson’s Trail of Tears, the U.S. government was anxious to further clear the way for white citizens to find to homes in the nascent Western landscape. The Bureau of Indian Affairs sent out writs of intent to the tribes that they were to, forthwith, resettle to U.S.-formed reservations. Those tribes that failed to heed this order were then assigned the label of ‘hostiles. The simple truth is that Custer’s orders were to simply move the ‘hostiles’ out of the way of expansion and move them to reservations. That’s all. But we have to step back.

In Neil’s telling, the Bureau used scouts to do official headcounts of tribesmen, women, and children in order to account for the number of Native Americans to be moved from ancestral homelands to government reservations. It was an early census-taking of the most primal sort. These accrued figures were then passed to the Army. Troops helmed by officers such as Custer were assembled according to numerical need and power of force, should it be required against the hostile natives. The Bureau counted tribal numbers of those living OFF the reservation in winter, of which there were very few. This is a critical point, per Mangum. A paltry number of tribal persons lived off the reservation in winter, period. Sheer survival dictated that life on the reservation, with food and shelter, was preferable to perishing in the subzero temperatures on the expansive plains. And so, these unwitting scouts counted those few beings and reported these numbers to the brass as gospel. By spring, armed with the Bureau mandate, the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux formed a loose and flexible alliance. They joined forces off the reservation lands, gathering in increasing numbers and compiling a superior and yes, substantial hostile force to meet the oncoming army. Word had also reached the tribes of bloody conflicts like the Fetterman massacre and bloodletting at the Rosebud reservation. They prepared and they waited for an inevitable clash.

From Neil Mangum’s perspective, this is the part of the story that was too often glossed over in the history books. Custer’s courage was, in fact, absolutely real. He followed his marching orders to the letter. And sacrificed his life to what amounted to a clerical counting error. The diverse tribes gathered between 2,000 to 2,500 capable, battle-ready horsemen to meet Custer’s pitiful column of 250. A second column led by General Reno raised the total to nearly 600 cavalry, coming from opposite directions, vastly ill-suited to the open terrain and fatally outnumbered. In essence, Custer was doomed before he saddled his horse that day. And yet, Neil says, “If Little Bighorn represents the zenith of Sioux and Cheyenne power, it also punctuates the timeline when Sioux and Cheyenne undergo rapid decline. Less than a year later, even the most resolute Indians who had destroyed Custer faced defeat and starvation. Most of them submitted to reservation confinement. A few under the leadership of the likes of Sitting Bull and Gall elected self-imposed exile in Canada.” There was no happy or victorious end for the Union army or the tribes.

Neil makes a strong and salient point for responsible and responsive historical interpretation. “Listening. Hearing. Historical interpretation.” He spent his first nine years at the Custer Battlefield National Battlefield seeking out and listening to the native voices around him. Touring the battlefield with tribal elders, learning where their ancestors had fallen. He made a determined effort to use Native American interpreters to add depth and veracity to tours and bolster exhibits. Before his arrival in the plains, Neil explains, “In the early decades of what was then called Custer Battlefield National Monument, the Indian side of the story was neglected or certainly muted.”

And then he got a call to pack his car again. This time, he and his wife headed southwest to New Mexico and Santa Fe, where he worked side by side with renowned historian of Native Americans, Melody Webb, methodically adding heft to his understanding of and compassion for the tribes of the Southwest region, and perhaps by extension, the Native Americans at Little Bighorn.

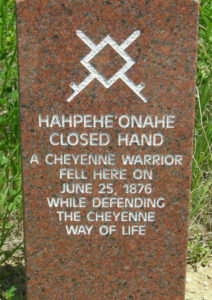

Once again, fate intervened and he returned to Little Bighorn a decade later, this time as the park’s superintendent, a promotion that changed everything for Neil. A plethora of voices, tribal, white, rangers and historians, skilled amateurs, and weekend buffs were added together in a vibrant stew to open up and broaden the battlefield story. New red granite markers were placed where tribal members fell in 1876. What was once called the Custer Battlefield National Monument became the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Mangum goes on to say, “Today, the battlefield story is not so much about the strong personalities of Custer or Sitting Bull. Rather, it is an aggregate of hundreds of personal stories, told by men and women on both sides. They all fought for preservation and a way of life, oftentimes distinct and culturally different. That, as a nation, is who we are. Little Bighorn is a microcosm of who we are.”

Newly expanded exhibits were added to the visitor center. Native voices now grace audio recordings for self-guided tours. The work continues. And Mangum offers an exciting tidbit. A new visitor center is planned, wisely using the current building footprint to avoid any (further) destruction to the battlefield site. Completion is targeted for the 150th anniversary of the Battle at Little Bighorn, June 25-26, 2026. He’ll be there.

Neil Mangum now lives in Arizona, retired but rarely idle. He leads popular tours for BGES—including the upcoming “Custer’s Trail,” on June 20–29, 2021. And he continues to listen closely to those speaking around him. For Neil Mangum, history is clarified and corrected by interpretation and avid attention to the sound of disparate voices.